Although the academic literature has tended to focus on the most appropriate technique for valuation, it is important to remember that there are many variants of each technique and these too may have important implications. Techniques vary in terms of their mode of administration (e.g., interview or self-completion, computer or paper administration), search procedures (e.g., iteration, titration, or open-ended), the use of props and diagrams, time allowed for reflection, and individual versus group interviews. There have been few publications in the health economics literature comparing these alternatives, but what evidence there is suggests that health state values vary considerably between variants of the same technique (Brazier et al., 2007).

There is evidence that the wording of questions affects the answers. This finding has a number of implications. To cite two examples, first, it demonstrates the importance of using a common variant to ensure comparability between studies. Second, there might be scope for correcting for some of these differences if they prove to be systematic. However, there has been little of this work to date.

More fundamentally, this evidence suggests that people do not have well-defined preferences over health prior to the interview, but rather their preferences are constructed during the interview. This would account for the apparent willingness of respondents to be influenced by the precise framing of the question. This may be a consequence of the cognitive complexity of the task. Evidence from the psychology literature suggests that respondents faced with such complex problems tend to adopt simple-decision heuristic strategies (Lloyd, 2003). Much of the interview work has been done using cold-calling techniques. There is a strong case for allowing respondents more time to learn the techniques, to ensure they understand them fully, and to allow them more time to reflect on their health state valuations. An implication may be to move away from the current large-scale surveys of members of the general public involving one-off interviews, to smaller-scale studies of panels of members of the general public who are better trained and more experienced in the techniques and who are given time to fully reflect on their valuations (Stein et al., 2006).

Who Should Value Health?

Values for health could be obtained from a number of different sources including patients, their carers, health professionals, and the community. Health state values are usually obtained from members of the general public trying to imagine what the state would be like, but in recent years the main criticism of this source has come from those who believe values should be obtained from patients.

The choice of whose values to elicit is important, as it may influence the resulting values. A number of empirical studies have been conducted that indicate that patients with firsthand experience tend to place higher values on dysfunctional health states than do members of the general population who do not have similar experience, and the extent of this discrepancy tends to be much stronger when patients value their own health state. There are a number of possible contributing factors for observed differences between patient and general population values including poor descriptions of health states (for the general population), use of different internal standards, or response shift and adaptation.

Why Use General Population Values?

The main argument for the use of general population values is that the general population pays for the service. However, while members of the general population want to be involved in health-care decision making, it is not clear that they want to be asked to value health states specifically. At the very least, it does not necessarily imply the current practice of using relatively uninformed general population values.

Why Use Patient Values?

A common argument for using patient values is that patients understand the impact of their health on their well-being better than someone trying to imagine it. However, this requires a value judgment that society wants to incorporate all the changes and adaptations that occur in patients who experience states of ill health over long periods of time. It can be argued that some adaptation may be regarded as laudable, such as skill enhancement and activity adjustment, whereas cognitive denial of functional health, suppressed recognition of full health, and lowered expectations may be seen as less commendable. Furthermore, there may be a concern that patient values are context based, reflecting their recent experiences of ill health and the health of their immediate peers. In addition, there are practical problems in asking patients to value their own health, many of whom will by definition be quite unwell.

Finally, to obtain values on the conventional 0 to 1 scale required for QALYs, valuation techniques require patients to compare their existing state to full health, which they may not have experienced for many years. For patients who have lived in a chronic health state like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or osteoarthritis, for example, the task of imagining full health is as difficult as a healthy member of the general population trying to imagine a poor health state.

A Middle Way – Further Research

It has been argued that it seems difficult to justify the exclusive use of patient values or the current practice of using values from relatively uninformed members of the general population. Existing generic preference-based measures already take some account of adaptation and response shift in their descriptive systems, but whether this is sufficient is ultimately a normative judgment. If it is accepted that the values of the general population are required to inform resource allocation in a public system, it might be argued that respondents should be provided with more information on what the states are like for patients experiencing them.

Generic Preference-Based Measures Of Health

Description Of Instruments

Generic preference-based measures have become one of the most widely used set of instruments for deriving health state values. As already described, generic preference based measures have two components: the first is their descriptive system that defines states of health and the second is an algorithm for scoring these states. The number of generic preference-based measures has proliferated over the last two decades. These include the QWB scale; Rosser Classification of illness states; HUI Marks 1, 2, and 3 (HUI1, HUI2, and HUI3); EQ-5D; 15D; SF-6D, a derivative of the SF-36 and SF-12; and AQOL (see Brazier et al., 2007 for further details of each of these instruments and their developers). This list is not complete and does not account for some of the variants of these instruments, but it includes the vast majority of those that have been used.

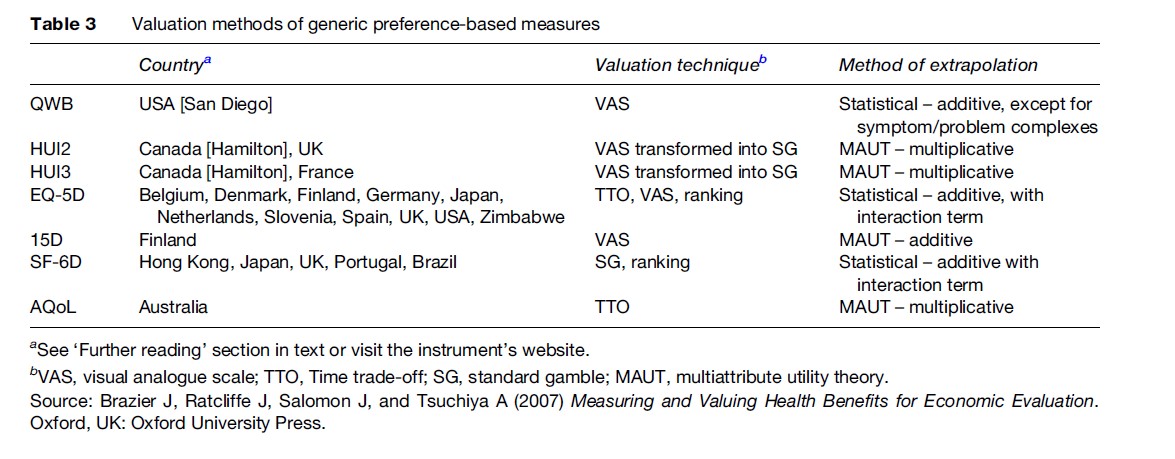

While these measures all claim to be generic, they differ considerably in terms of the content and size of their descriptive system, the methods of valuation, and the populations used to value the health states (though most aim for a general population sample). A summary of the main characteristics of these seven generic preference based measures of health is presented in Table 2 and Table 3. Table 2 summarizes the descriptive content of these measures including their dimensions and dimension levels. Each instrument has a questionnaire for completion by the patient (or proxy), or administration by interview, that is used to assign them a health state from the instrument’s descriptive system. These questions are mainly designed for adults, typically 16 or older, although the HUI2 is designed for children. Table 3 summarizes the valuation methods used in terms of the valuation technique and the method of modeling the preference data.

Comparison Of Measures

The agreement between measures was generally found to be poor to moderate (about 0.3–0.5 as measured by the intraclass correlation coefficient). Whereas differences in mean scores have often been found to be little more than 0.05 between SF-6D, EQ-5D, and HUI3, this mean statistic masks considerable differences in the distribution of scores.

Given the differences in coverage of the dimensions and the different methods used to value the health states, it is not surprising the measures have been found to generate different values. The choice of generic measure has been a point of some contention, since the respective instrument developers have academic and in some cases commercial interests in promoting their own measure. The recommended approach to instrument selection has been to compare their practicality, reliability, and validity (Brazier et al., 2007). Although all these instruments are practical to use and achieve good levels of reliability, the issue of validity has been more contentious and difficult to prove.

Validity can be broken down into the validity of the descriptive system of the instrument, the validity of the methods of valuation, and the empirical validity of the scores generated by the instrument. In terms of methods of valuation, the QWB and the 15D would be regarded by many health economists as inferior to the other preference-based measures due to their use of VAS to value the health descriptions. HUI2 and HUI3 would be preferred to the EQ-5D by those who regard the SG as the gold standard, but this is not a universally held view in health economics. A further complication is that the SG utilities for the HUIs have been derived from VAS values using a power transformation that has been criticized in the literature (Stevens et al., 2006). There is evidence in terms of descriptive validity that some measures perform better for certain conditions than others (Brazier et al., 2007); however, there are no measures that have been shown to be better across all conditions. The validity of the descriptive system relates to the condition and treatment outcomes associated with the treatment being evaluated.

Conclusions

This research paper has described the key features of the instruments available for estimating health state values for calculating QALYs. It has shown the large array of methods available for deriving health state values. This richness in methods comes at a price, because the analyst, and perhaps more importantly the policy maker, must decide on the methods to use for informing resource allocation decisions. Some of the issues raised can be resolved by technical means, using theory (such as the use of VAS) or empirical evidence (such as the descriptive validity of different generic measures). Others require value judgments about the appropriateness of using general population instead of patient values.

For policy makers wishing to make cross-program decisions, the Washington, DC panel on Cost Effectiveness in Health and Medicine and some other public agencies (such as NICE) have introduced the notion of a reference case that has a default for one or other of the (usually generic) measures. Given that more than one measure is likely to be used for the foreseeable future, and perhaps for good reason, there is a need for further research to focus on mapping or ‘cross walking’ between measures.

Bibliography:

- Brazier J, Roberts J, and Deverill M (2002) The estimation of a preference-based single index measure for health from the SF-36. Journal of Health Economics 21(2): 271–292.

- Brazier J, Ratcliffe J, Salomon J, and Tsuchiya A (2007) Measuring and Valuing Health Benefits for Economic Evaluation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.