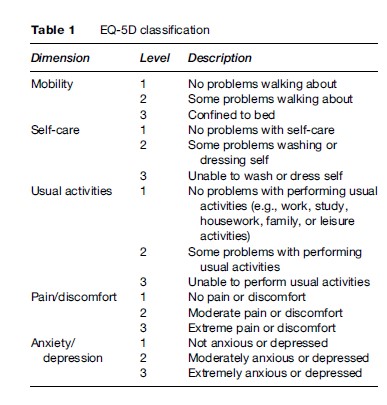

To calculate QALYs it is necessary to represent health on a scale in which death and full health are assigned values of 0 and 1, respectively. Therefore, states rated as better than dead have values between 0 and 1 and states rated as worse than dead have negative scores that in principle are bounded by negative infinity. One of the most commonly used instruments for estimating the value of the ‘Q’ in the QALY is a generic preference-based measure of health called the EQ-5D (Brooks et al., 2003). This instrument has a structured health state descriptive system with five dimensions of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/ depression (Table 1). Each dimension has three levels: no problem (level 1), moderate or some problem (level 2), and severe problem (level 3). Together these five dimensions define a total of 243 health states formed by different combinations of the levels (i.e., 35), and each state is described in the form of a five-digit code using the three levels (e.g., state 12321 means no problems in mobility, moderate problems in self-care, etc.). It can be administered to patients or their proxy using a short one-page questionnaire with five questions.

The EQ-5D can be scored in a number of ways depending on the method of valuation and source country, but the most widely used to date is the UK York TTO Tariff shown in Table 2. This population value set was obtained using the time trade-off (TTO) method with a sample of about 3000 members of the UK general population; similar tariffs have been estimated for other countries, including the United States. Different valuation methods and the appropriateness of obtaining values from the general population are reviewed later in this research paper.

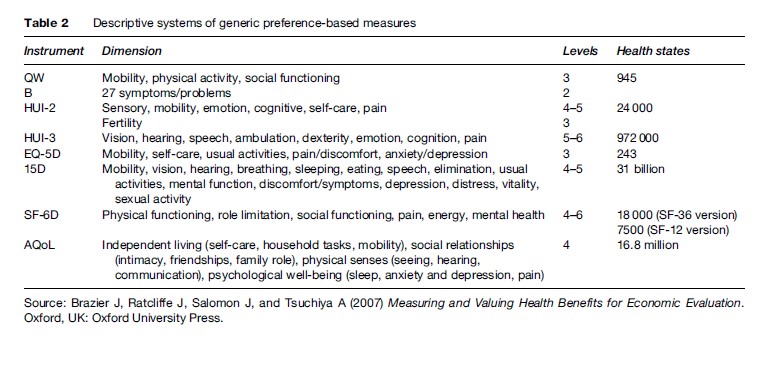

The EQ-5D provides a useful starting point for the rest of this research paper, because it demonstrates the key features of any method for measuring and valuing health. Underpinning the EQ-5D and similar instruments are a number of core methodological questions: How should health be described, how should it be valued, and who should provide the values? The first part of the question concerns the aspects of health (and/or quality of life) that should be covered by the measure. The next part concerns the valuation technique that should be used. The EQ-5D has been valued using TTO and visual analogue scale (VAS). Other generic preference-based measures such as the HUI3 and SF-6D used the standard gamble (SG) method, which some have argued should be the gold standard method of valuation in this field. The last part of the question concerns the source of values, and whether they should be obtained from patients themselves, their carers and medical professionals, or members of the general population. The remainder of this research paper addresses these three questions. (For discussion on whether the QALY is an appropriate measure and how QALYs should be aggregated and used to inform health policy, see Brazier et al., 2007.)

How Should Health Be Described?

There are two broad approaches to describing health for deriving health state values. One is to construct a custom-made description of the condition and/or its treatment and the other is to use a standardized descriptive system (such as the EQ-5D). A bespoke description, sometimes referred to as a vignettes in the literature, can take the form of a text narrative or a more structured description using a bullet point format. More recently researchers have begun to explore alternative narrative formats, such as the use of videos or simulators. The use of custom-made vignettes was more common in the early days of obtaining health state values, however, in recent years the standardized descriptive systems have tended to dominate.

The other approach has been to use generic preference based measures of health such as the EQ-5D. These have two components, the first a system for describing health or its impact on quality of life using a standardized descriptive system, and the second an algorithm for assigning values to each state described by the system. A health state descriptive system is composed of a number of multilevel dimensions that together describe a universe of health states (such as the EQ-5D described earlier). Generic instruments have been developed for use across all groups by focusing on core aspects of health.

Generic preference-based measures have become the most widely used and this stems from their ease of use, their alleged generic properties (i.e., validity across different patient groups), and their ability to meet a number of requirements of agencies such as the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Furthermore, they come ‘off the shelf,’ with a questionnaire and a set of weights for each health state defined by the classification already provided. The questionnaires for collecting the descriptive data can be readily incorporated into most clinical trials and routine data collection systems with little additional burden for respondents, and the valuation of their responses can be done easily using the scoring algorithms provided by the developers.

However, there are concerns about the sensitivity of the generics and their relevance for some conditions. As a result, there has been work to develop condition-specific descriptive systems (Brazier et al., 2007) and there continues to be an interest in using custom-made vignettes. This raises the question as to whether health state utilities derived from specific descriptive systems are generalizable. This is important for economic evaluations in which the purpose is often to inform resource allocation decisions across patient groups. Even if values are obtained using the same techniques and from similar populations, differences may persist due to preference interactions between dimensions in the descriptions and those outside the system. The impact of asthma on health state utility values, for example, may be altered by the presence of pain from a comorbid condition. Of course, this problem exists for generic descriptive systems; it is just more likely to be a problem with specific systems. Ultimately it is a trade-off between the greater relevance and sensitivity of some specific systems and the limitations on generalizability.

There are also important issues about the appropriate conceptual basis for a descriptive system; some instruments cover quite narrowly defined aspects of impairment and symptomology associated with medical conditions, while others consider a higher level and broader conception of quality of life.

Valuation Techniques

To be used in economic evaluation, health state valuations need to be placed on a scale ranging from 0 to 1, where 0 is for states regarded as equivalent to dead and 1 is for a state of full health. Within the health state valuation process it is also necessary to allow for states that could be valued as worse than being dead. The three main techniques for valuing health states are the SG, the TTO, and the VAS. This section describes how each technique can be used to value chronic health states.

The Visual Analogue Scale (Vas)

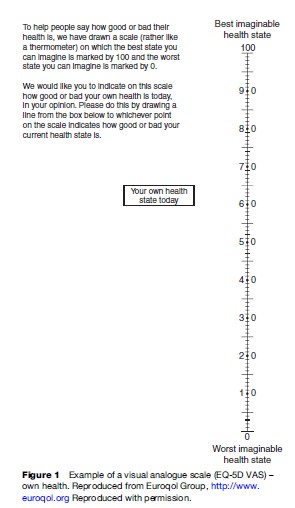

The VAS is usually represented as a line with well-defined endpoints, on which respondents are able to indicate their judgments, values, or feelings (thus it is sometimes called a ‘feeling’ thermometer). The distances between intervals on a VAS should reflect an individual’s understanding of the relative differences between the concepts being measured. VAS is intended to have interval properties, so that the difference between 3 and 5 on a 10-point scale, for example, should equal the difference between 5 and 7.

In the health context, VAS has been widely used as a measure of symptoms and various domains of health including the direct measurement of a patient’s own health or as a means of valuing generic health state classifications including the Quality of Well-Being scale (QWB) (Kaplan and Anderson, 1988), the HUI (Feeny et al., 2002) and the EQ-5D (Brooks et al., 2003). Figure 1 presents an example of the VAS developed by the Euroqol group. VAS can also be used to elicit the value attached to temporary health states (e.g., those lasting for a specified period of time after which there is a return to good health in contrast to chronic health states which are assumed to last for the rest of a person’s life) and states considered worse than death.

The Standard Gamble (SG)

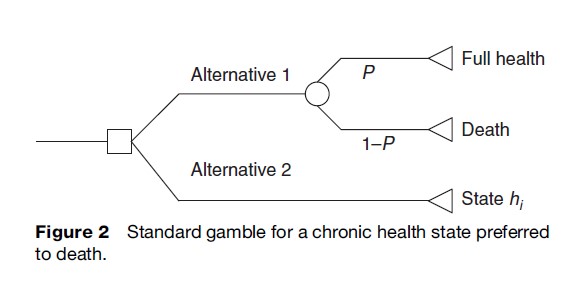

The SG comes from expected utility theory, which postulates that individuals choose between prospects – for example, different ways of managing a medical condition – in such a way as to maximize their ‘expected’ utility. The SG method gives the respondent a choice between a certain intermediate outcome and the uncertainty of a gamble with two possible outcomes, one of which is better than the certain intermediate outcome and one of which is worse. The SG task for eliciting the value attached to health states considered better than dead is displayed in Figure 2. The respondent is offered two alternatives. Alternative 1 is a treatment with two possible outcomes: either the patient is returned to normal health and lives for an additional t years (probability = P), or the patient dies immediately (probability = 1-P). Alternative 2 has the certain outcome of chronic state hi for life (t years). The probability P of the best outcome is varied until the individual is indifferent between the certain intermediate outcome and the gamble. This probability P is the utility for the certain outcome, state hi. This technique is then repeated for all intermediate outcomes. The SG can also be modified to elicit the value attached to health states considered worse than death and temporary health states.

The SG technique has been widely applied in the decision-making literature and has also been extensively applied to medical decision making, including the valuation of health states, in which it has been used (indirectly via a transformation of VAS) to value the HUI2 and HUI3 (Torrance et al., 1996; Feeney et al., 2002) and to directly value SF-6D (Brazier et al., 2002) and a number of condition-specific health state scenarios or vignettes (Brazier et al., 2007). There are many variants of the SG technique that differ in terms of the procedure used to identify the point of indifference, the use of props, and the method of administration (e.g., by interviewer, computer, or self-administered paper questionnaire).

The Time Trade-Off (TTO)

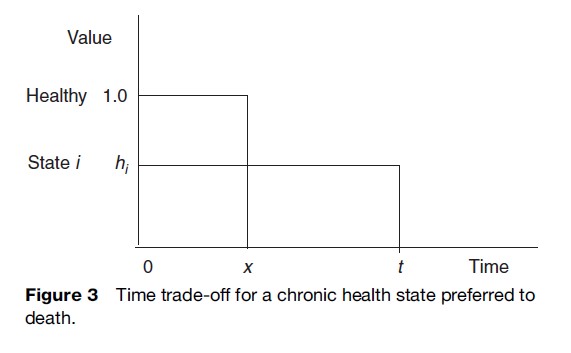

The TTO technique was developed specifically for use in health care in an effort to overcome the problems associated with SG in explaining probabilities to respondents. TTO asks respondents to choose between two alternatives of certainty rather than between a certain outcome and a gamble with two possible outcomes. The application of TTO to a chronic state considered better than dead is illustrated in Figure 3.

The approach involves presenting individuals with a paired comparison. For a chronic health state preferred to death, alternative 1 involves living for period t in a specified but less than full health state (state hi). Alternative 2 involves full health for time period x where x < t. Time x is varied until the respondent is indifferent between the two alternatives. The score given to the less than full health state is then x/t. The TTO task can be modified to consider chronic health states considered worse than death and temporary health states. In common with SG, there are numerous variants of TTO using different elicitation procedures, props (if any), and modes of administration.