Whether practicing in generalist, specialist, or advanced practice roles, nurses are making a considerable and positive impact on the provision of health services. There is a well-established and expanding body of research evidence documenting the effectiveness of their care. For instance, outcome research indicates that care provided by NP/ APNs is equivalent to that of physicians (Brown and Grimes, 1995; Mundinger et al., 2000). Further, care delivered by NP/APNs has been associated with improved patient satisfaction, reduced hospital lengths of stay, improved quality of life, lower hospital re-admission rates, better health education, and decreased health-care costs (Brown and Grimes, 1995; Kinnersley et al., 2000; Mundinger et al., 2000; Ritz et al., 2000; Venning et al., 2000; Naylor et al., 2004). There are also a significant number of research studies linking higher numbers and a richer mix of qualified/registered nurses to reductions in patient mortality, rates of respiratory, wound, and urinary tract infections, number of patient falls, incidence of pressure sores, and medication errors (see West et al., 2004).

When natural or manmade disasters strike, nurses are often the first wave of responders and major contributors to the restoration of public health services post-disaster. They make a significant contribution to national and international efforts targeting the health and social problems of refugees, displaced persons, and migrants resulting from disasters, political turmoil, and civil strife.

Nurses make a valuable and unique contribution to health services through research. They employ both qualitative and quantitative research methodologies to evaluate, validate, and refine existing knowledge and to generate new knowledge in relation to nursing and health services. The knowledge generated through nursing research is used to inform nursing education, practice, and management, to shape health policy, and to enhance the health and well-being of populations.

Not surprisingly, nurses are also found at the forefront of innovative discoveries in health care. They use their creative capacity to find solutions to both old and new problems many of which have led to improvements in the health of patients, the day-to-day work life of nurses, and the way in which health services are delivered. Increasingly nurses are being called on by the pharmaceutical industry, manufacturers of medical devices, and health information technology suppliers to participate in, or lead, new product research and development. Internationally, novel solutions by nurses abound, some of which are being captured in the International Council of Nurses Innovations Database.

Professional Nursing Organizations

Professional organizations have long been an integral part of the nursing profession providing a medium through which nurses with common goals and interests work collectively for the benefit of society and the advancement of the profession (ICN, 1996a).

Nurses join professional organizations for various reasons. For example, some see membership as the first step toward becoming identified with the profession, while others view membership as a way to stay current on professional issues and developments, to access networking opportunities, to exchange ideas, information, and experiences with colleagues and/or as a means to achieve continuing professional growth and education (ICN, 1996a). A nurse may choose to hold membership in one or more professional organizations or associations.

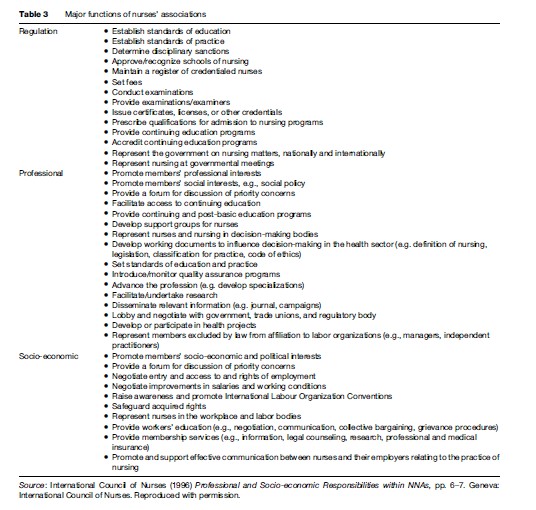

In all countries, the nursing profession is organized in the form of national nurses’ associations. In some countries, these associations are federations of affiliated provincial or state nursing organizations while in others they are nonfederated entities. The functions of such associations are diverse, but can be broadly categorized as regulatory, professional, and socioeconomic. An association may perform one or more of these functions. The most common models seen today are: (1) professional association and regulatory body; (2) professional association and regulation responsibilities for continuing and post-basic education and qualifications; (3) professional association with programs also focused on members’ individual interests and concerns; and (4) professional association and socioeconomic welfare organization/negotiating body (ICN, 1996b).

The purpose and functions of an association may be influenced by a number of local external factors. These include the health-care system in which the association is located, legislation and societal changes, the type of association, the role and social status of nurses, the role of other nursing associations, and globalization and regionalization (ICN, 1996a). Some examples of major functions that may be carried out by nurses’ associations are highlighted in Table 3.

There are also a number of well-established specialty nursing organizations that have evolved over the past several decades as the profession has become more specialized. Such organizations are most often formed around a defined area of specialty nursing practice, such as oncology, gerontology, or public health. They may be autonomous organizations, or they may form a branch of a larger national nursing association. The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, established in 1969, is one the world’s largest specialty nursing organizations.

Additionally, there are organizations that speak for nursing at the regional and global levels. For example, the Caribbean Nurses Organization, founded in 1957, is the regional voice for nursing in the Caribbean. At the global level, the International Council of Nurses is the largest and oldest organization for nurses.

Nursing organizations may also unite to form interdisciplinary alliances with other organizations. One such example is the World Health Professions Alliance which brings together dentistry, medicine, nursing, and pharmacy through their representative international organizations, the International Council of Nurses, the International Pharmaceutical Federation, the World Dental Federation, and the World Medical Association. Together, they represent the interests of more than 20 million health professionals worldwide.

Historically, professional organizations have played an important role in nursing’s development. Today, nursing organizations and associations, whether operating at the local, national, regional, or international level, remain committed to promoting improvements in the standards of nursing care and to advancing the profession, health services, and the health and well-being of society as a whole.

Global Nursing Workforce Shortage

One of the most pressing challenges facing health-care systems and the nursing community worldwide is the growing shortage of nurses. Globally, there is wide acknowledgment that the scarcity of nurses, combined with the short supply of other health workers, is rapidly establishing itself as a major threat to public health in many nations. In a number of countries, the shortage of health workers, particularly nurses, is placing a tremendous burden on already overtaxed health systems and is creating a major barrier to the provision of essential health services. For others, notably the least developed countries, inadequate human resources have become the most significant constraint on the attainment of national and international health and development goals.

Current and predicated nursing shortages, in both developed and developing countries, have been reported by a number of organizations including the World Health Organization, the World Bank, the Pan American Health Organization, the International Council of Nurses, Physicians for Human Rights, and the Global Health Trust. Nowhere in the world is the shortage said to be more pronounced or severe than in sub-Saharan Africa where deficiencies in supply are exacerbated by the international movement of nurses to more developed countries in search of better working conditions and quality of life. In countries of this subregion, it is not uncommon to find one nurse responsible for providing care to 50 to 100 patients at one time.

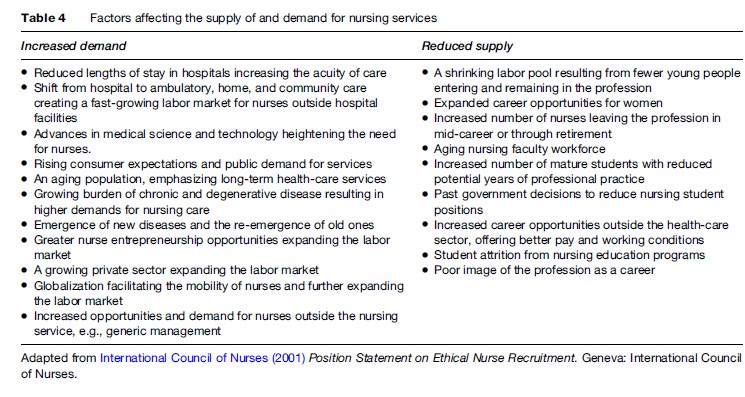

Nursing shortages are not a new phenomenon. A number of developed countries, notably the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States, have cycled through shortages in the past frequently as a result of demand for nursing services exceeding supply. However, the current shortage is unlike those of the past, as health systems worldwide are experiencing pressures exerted on both the supply of and demand for nurses. While the demand for health services and nurses is growing due to demographic and epidemiological changes, among other factors, the supply of available nurses in many countries is diminishing and is predicted to worsen in the absence of countermeasures.

Inadequate human resources planning and management, including poor deployment practices, coupled with high attrition from the workforce (due to poor work environments, low professional satisfaction, and inadequate remuneration), international and internal migration, the impact of HIV/AIDS, and chronic underinvestments in health human resources are major factors driving the current nursing shortage. Additional factors affecting the supply of, and demand for nursing services are highlighted in Table 4.

Ironically, today’s nursing shortages exist parallel with the unemployment of thousands of nurses, particularly in parts of Asia, Latin America, Eastern Europe, and Africa. High rates of unemployment are primarily the result of employment/hiring freezes caused by loan conditions placed on borrowing countries by donors and international monetary institutions. As well, a number of countries report underemployment of nurses due to policies and practices that deter them from obtaining fulltime employment.

In a number of countries, nursing shortages coexist with the shortage of nurse educators. These shortages are the result of an aging nursing faculty workforce and a limited pool of younger faculty to replace those retiring. The reduction in the availability of faculty is serving to intensify the current nursing shortage by reducing the ability of education providers to increase their intake of applicants to meet future demand.

The international recruitment and migration of nurses has, in the past decade, become a growing concern for national governments, nursing organizations, employers, and the global health and development community. The World Health Assembly, the World Health Organization’s highest decision-making body, has repeatedly drawn attention to the international migration of skilled health workers and the challenges it poses for health systems, particularly in resource-poor countries.

While not a new phenomenon, the international movement of nurses from developing to developed countries is accelerating. Increasingly, nurses are choosing to leave their native country seeking better working conditions and quality of life elsewhere. Their movement across national borders is attributed to a number of push and pull forces. On the push side are factors such as difficult working environments (often characterized by heavy workloads, risk of exposure to violence, abuse and occupational hazards, lack of autonomy and decision-making authority, limited access to supplies, medication, and technology), low pay, poor career advancement opportunities, lack of non-monetary incentives, and sociopolitical unrest. On the pull side, nurses may migrate to other countries in search of better opportunities for professional development, safer and better equipped working environments, improved remuneration and incentives, greater sociopolitical stability, and a desire for greater professional autonomy.

However, large-scale, and often aggressive international recruitment by developed countries is cited as a major contributing factor to the current high levels of nurse migration. Developed countries have increasingly come to rely on recruiting foreign-trained nurses to fill their domestic shortfalls instead of addressing in-country recruitment and retention issues. The effects of this practice on developing countries include a loss of skilled human capital and economic investments and an inability to adequately meet national health service needs.

Unethical recruitment practices are occurring worldwide and there is a lack of regulatory oversight at both national and international levels. The International Council of Nurses, the World Health Organization, and the Commonwealth Secretariat, while supporting the right of nurses to migrate, have all independently made calls in the form of position statements, resolutions, and codes of practice for better monitoring and more ethical approaches to nurse migration.

In 2005, the International Council of Nurses and the Commission on Graduates of Foreign Nursing Schools teamed up to establish the International Centre on Nurse Migration – a global resource for the development, promotion, and dissemination of research, policy, and information on nurse migration. The Centre works to address gaps in policy, research, and information with regard to the migrant nurse workforce, including screening and workforce integration.

Internationally, the scarcity of nurses is having a negative impact on patients, health systems, and nursing personnel and there is a significant body of research documenting its impact. For instance, nursing shortages have been linked to increased mortality, accidents, injuries, cross-infection, and adverse postoperative events.

The International Council of Nurses has recently completed a major two-year research and global consultation initiative to document the state of today’s nursing workforce and to inform future policy making. Through its work, the Council has identified five priority areas that require policy attention in the immediate, short, and long term, at both national and international levels. These areas are: macroeconomic and health sector funding policies; workforce policy and planning, including regulation; positive practice environments and organizational performance; recruitment and retention; addressing incountry maldistribution, and out-migration; and nursing leadership. Full details of this work can be obtained on the ICN website.

In 2006, ICN established the International Centre for Human Resources in Nursing. The Centre, whose ultimate aim is to bring about improvements in the quality of patient care through the provision of better managed health care and nursing services, serves as an online gateway to comprehensive information, resources, and analysis on nursing human resources policy, management, and practice.

The World Health Assembly has repeatedly recognized the essential role nurses and midwives play in the provision of effective health services and has made calls, through numerous resolutions, to strengthen the workforce. In 2006, during the 59th session of the Assembly, 192 member states unanimously adopted a major resolution to strengthen nursing and midwifery. The resolution urges member states to commit to strengthening the workforce by:

(1) establishing comprehensive programmes for the development of human resources which support the recruitment and retention, while ensuring equitable geographical distribution, in sufficient numbers of a balanced skill mix, and a skilled and motivated nursing and midwifery workforce within their health services; (2) actively involving nurses and midwives in the development of their health systems and in the framing, planning and implementation of health policy at all levels, including ensuring that nursing and midwifery is represented at all appropriate governmental levels, and have real influence; (3) ensuring continued progress toward implementation at country level of WHO’s strategic directions for nursing and midwifery; (4) regularly reviewing legislation and regulatory processes relating to nursing and midwifery in order to ensure that they enable nurses and midwives to make their optimum contribution in the light of changing conditions and requirements; (5) to provide support for the collection and use of nursing and midwifery core data as part of national health information systems; (6) to support the development and implementation of ethical recruitment of national and international nursing and midwifery staff. (WHO, 2006: 1–2)

Conclusion

Nurses are the single largest group of health-care professionals in most countries. As such they are a vital input in all health systems. Internationally, nurses are evolving their roles and reconfiguring their practice to meet the complex challenges facing health systems and the changing health and social needs of individuals, families, groups, populations, and communities. Ensuring their adequacy in numbers, skills, and distribution is paramount to quality, equity, safety, and cost-effectiveness in patient care and health services around the world.

Bibliography:

- Brown SA and Grimes DE (1995) A meta-analysis of nurse practitioners and nurse midwives in primary care. Nursing Research 44(6): 332–339.

- Canadian Nurses Association (2006) Report of 2005 Dialogue on Advanced Nursing Practice. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Nurses Association.