Introduction

The lymphomas encompass a group of distinct hematologic malignancies which arise from T and B lymphocytes. These lymphatic neoplasms are typically categorized as Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Hodgkin lymphomas (HL) are derived from B cells or their progeny and are distinguished by the presence of multinucleated Reed-Sternberg cells. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) are classified by the World Health Organization (Jaffe and Harris, 2001) into 21 subtypes of B-cell and 15 subtypes of T-cell malignancies; NHL account for about 80–90% of all lymphomas. Lymphomas vary in their clinical presentation, course, treatment strategies, and long-term prognosis. The diversity of lymphoma subtypes suggests that etiologic factors may also differ, which contributes to the complexities of disease investigation. While some factors associated with an increased risk of these cancers have been identified, the elucidation of clear etiologic determinants and their mechanistic role in pathogenesis has been challenging.

Epidemiology

Worldwide, there are approximately 363 000 new cases of lymphoma annually, accounting for 3.3% of all cancers. Lymphoma claims about 195 000 lives each year. In the United States, lymphoma is the fifth most commonly occurring malignancy, with an incidence rate of 21.8 per 100 000. These cancers are slightly more common in males (26.0/100 000) than in females (18.4/100 000). Regarding race, Whites are at greater risk than Blacks. Hispanic ethnicity is associated with a decreased risk of lymphoma. Age-related patterns of disease differ between

HL and NHL. The incidence of NHL increases dramatically with aging. The median age of diagnosis is about 64 years, with only 3% of cases diagnosed under 20 years of age. In contrast, in developing countries, HL occur predominantly during childhood and incidence decreases with age. Among industrialized nations, the distribution of HL is bimodal with peaks in the third and fifth decades of life. There is significant disparity in lymphoma incidence related to economic development, with the highest rates observed in the most developed countries. Improved diagnostics, more complete reporting, greater exposures to potential environmental carcinogens, decreased childhood exposure to disease-related pathogens resulting in decreased immunity, and differences in racial distributions may account for these differences in disease incidence. The rates of different lymphoma subtypes are also subject to significant regional and international variation, likely due to differences in prevalence of etiologic factors.

Trends In NHL Incidence

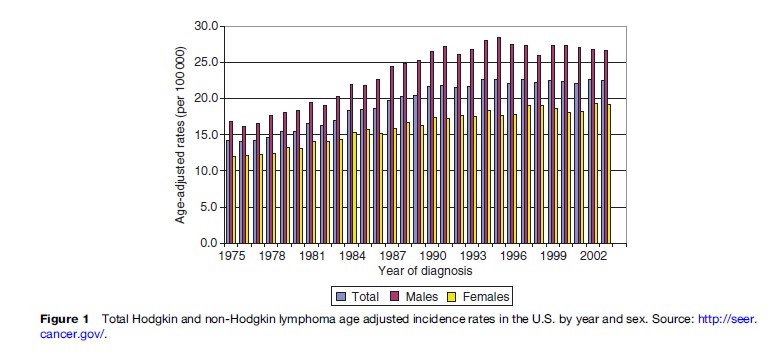

In most Western countries, unprecedented increases of about 3–4% each year in lymphoma incidence rates were observed from the 1970s to early in the 1990s, regardless of age, gender, or race (Figure 1).

In particular, incidence in males, ages 25–54, underwent dramatic escalation, mostly related to the HIV epidemic. A sharp rise in the incidence of extranodal primary lymphomas, particularly those of the brain, has also been documented. Factors that may account in part for this startling escalation in disease incidence include: improved cancer reporting, more sensitive diagnostic techniques particularly for borderline lesions, changes in classification of lymphoproliferative diseases, and, in particular, the increasing occurrence of AIDS-associated lymphomas.

Since 1995, lymphoma incidence among males in many countries has decreased, reflecting the improved immune status of those with HIV/AIDS resulting from the introduction of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART). However, available data suggest that the nonAIDS-related lymphoma incidence rates have continued to increase at a rate of approximately 1% per year, specifically among females, older males, and Blacks in the United States.

Clinical Aspects Of Lymphoma

The presentation of both HL and NHL depends on the specific lymphocytic tissue involved in the malignancy. Typically, disease is localized at onset and subsequently spreads by contiguity within the lymphatic system. Localized symptoms may be limited to a painless enlargement of a single lymph node. As the cancer disseminates, however, systemic symptoms develop which often mimic an infectious process. Fever, night sweats, fatigue, weight loss, shortness of breath, and itching skin are common. Diagnosis is made by histologic examination of biopsy tissue. Morphologic, immunophenotypic, genetic, and clinical characteristics also contribute to determination of the diagnostic classification and to the disease prognosis.

Confirmation of a diagnosis of HL requires the presence of multinucleated, polypoid Reed-Sternberg cells in the malignant tissue. HL presents in two forms: nodular lymphocyte predominant and the more classic form that includes nodular sclerosis, mixed cellular, lymphocyterich, and lymphocyte-depleted subtypes. A complete diagnostic work up is key to proper disease staging. Treatment is usually radiation therapy and/or combination chemotherapy. Outcomes of HL are particularly good with 5-year survival rates exceeding 90% for stages I and II and 80–90% for stages III and IV disease.

NHL vary from indolent to aggressive types. While slowly progressive and relatively responsive to chemotherapy, indolent tumors tend to wax and wane, repetitively relapse, and usually lead to eventual death. Aggressive lymphomas are highly proliferative and can be rapidly fatal, however, with new therapies, an increasing proportion of these malignancies are curable. Classification of NHL depends upon cluster differentiation antigen expression on the tumor cell surface; cytogenetic findings also add diagnostic and prognostic information. The International Prognostic Index provides distinct clinical and prognostic categories based on five demographic and clinical characteristics (age, performance status, serum lactate dehydrogenase, number of extranodal sites, and Ann Arbor stage). Therapeutic approaches for this disease are based on the specific lymphoma subtype, the stage of disease, the physiologic status of the patient, and the prognosis. While chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy are curative in some patients, many with primary or relapsed disease remain refractory to conventional treatments. For some subtypes, extended remissions have been achieved using either newly developed monoclonal antibodies directed against lymphoma cells (rituximab) or high-dose chemotherapy regimens paired with stem cell transplantation. Survival varies considerably by specific subtype; however, the overall 5-year survival rate for this malignancy now approaches 66%.

Lymphoma Pathogenesis

Lymphocytes arise from hematopoietic stem cells and undergo differentiation to a specific phenotype. These cells along with secondary lymphoid organs (lymph nodes, spleen, gastrointestinal and respiratory lymphoid tissues) are responsible for the immunologic response that protects against invasion by infectious and other foreign antigens. Immune regulation depends on a continuum of lymphoid cell growth, cell signaling, programmed cell death, and/or immune eradication. An imbalance in this complex system may initiate molecular processes that drive the malignant transformation of lymphocytes and promote proliferation of neoplastic cells; however, these processes are not well-understood. Normal T and B cell differentiation requires intricate B cell immunoglobulin and T cell receptor gene rearrangements, which are subject to spontaneous error. Chromosomal translocations are detected in up to 90% of lymphoid malignancies. Oncogenic viruses and environmental carcinogens may also independently generate genetic lesions. At a molecular level, these chromosomal translocations, deletions, and/or mutations may alter cell recognition, precipitate oncogene activation, and suppress repair mechanisms, thereby allowing clonal expansion of malignant T or B cells.

An emerging paradigm related to lymphomagenesis is that chronic antigenic stimulation, that is, a persistent inflammatory process, leads to increased B cell proliferation, thereby increasing the probability of random genetic errors. This theory is supported by the fact that increased risk of lymphoma has been clearly established in immunocompromised populations vulnerable to infection and, more recently, in those with specific chronic infections and autoimmune conditions. Common to such individuals is a persistent state of foreign or autoantigenic stimulation leading to a chronic inflammatory response involving a cascade of cellular and cytokine reactions that may provoke tissue injury, compensatory immunosuppression, and eventual tumor initiation. If the responsible antigen is infectious in nature, the pathogen itself may have the potential to infect a normal cell, integrate viral DNA into the host genome, and transform the cell into one that is malignant and self-replicating. Other environmental factors that independently lead to immunosuppression may act as cofactors in lymphomagenesis by further inhibiting the recognition and eradication of a malignant cell.

Etiology Of Lymphoma

Familial And Hereditary

Oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, and DNA repair genes have been shown to play an important role in carcinogenesis. While most genetic lesions that have been linked to cancers represent somatic mutations, inherited (germ line) genetic susceptibility to lymphoma is conceivable. Aggregation of lymphoma in families, while unusual, has been observed, suggesting a role of either heredity or shared environmental exposures in the etiology of lymphoma. Up to sevenfold increases in risk of lymphoma among individuals having a close relative with lymphoma or other lymphoproliferative diseases have been observed. Of note, Mack and colleagues (1995) reported a 99-fold increase in risk of HL among those having a monozygotic twin with HL. These associations, however, may merely reflect early identification of new cases in families with an increased awareness of lymphoma symptoms or may suggest shared environmental exposures among family members. While the role of polymorphisms in genes specifically responsible for immune regulation and function, such as apoptosis, DNA repair, and tumor necrosis factor, have been investigated, no clear association between any of these genetic mutations and lymphoma risk has been identified. In general, familial lymphomas account for less than 5% of all cases; thus, the risk of lymphoma attributable to hereditary factors is likely to be low.

Immune Dysregulation

An important role of the immune system in the occurrence of lymphoma has been well-established. Risk of lymphoma is clearly increased in conditions of immune dysregulation, be it primary immunodeficiency, iatrogenic immunosuppression, autoimmune disease, or acquired immunodeficiency. Persistent immunologic stimulation and cytokine production, reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, and gene rearrangements appear to be sequelae that most often herald lymphomagenesis.

Primary Immunodeficiency

Among individuals with primary immunodeficiency, the risk of lymphoma ranges from 10–25%. These conditions are characterized by genetic defects that interfere with DNA repair and cell-mediated immunity. Specifically, hereditary immunodeficiencies such as Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome and ataxia telangiectasia are accompanied by a 10–15% absolute risk of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Since the T cell response is so important in controlling EBV infection, it is not surprising that many of these tumors are EBV-associated. These neoplasms are aggressive, primarily extranodal, and frequently involve the central nervous system.

Iatrogenic Immunosuppression

Individuals with secondary immunosuppression, most often drug-induced to prevent organ rejection in transplant recipients, experience dramatic increases in lymphoma risk. Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) is characterized by polyclonal and monoclonal lesions derived from mutated B cells. The magnitude of risk of PTLD varies depending on the degree, duration, and type of immunosuppression. Opelz and Dohler (2004) conducted a large international study of 195 938 patients who received a solid organ transplant. These investigators found that the relative risk of lymphoma among organ transplant recipients at 5 years compared to the normal population was 239.5 for heart–lung recipients, 58.6 for lung recipients, 34.9 for pancreas, 29.9 for liver, 27.6 for heart, and 12.6 for cadaveric kidney. Chronic antigenic stimulation from the allograft on a backdrop of drug induced immunosuppression is the likely mechanism for these lymphoid malignancies. As with primary immunodeficiency, the hallmark of these lymphomas is high-grade, often EBV-positive tumors with a proclivity for extranodal sites, especially the brain. While this condition often develops within the first year after an allograft, when immunosuppression is usually severe, time to lymphoma development had no impact on patient survival. Historically, outcomes with PTLD have been poor, with 1-year mortality approaching 50%. Recent efforts to reduce immunosuppressive drugs and treat with rituximab have led to a 64% response rate in PTLD.

Autoimmune Conditions

It has been difficult to delineate the deleterious effects of immunosuppression alone from the impact of persistent inflammation in the development of lymphoma among individuals having autoimmune conditions that often require treatment with immunosuppressive agents. For example, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosis, Sjogren’s syndrome, and celiac disease all carry an increased risk of both HL and NHL. Patients with the latter two diseases are generally not treated with immunosuppressants, so their risk of lymphoma can be attributed to the underlying autoimmune disease. On the other hand, patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosis frequently receive immunosuppressive therapy for extended periods of time. The increased risk of lymphoma seen in this population may therefore be partly incurred from the disease itself and partly from its treatment. Askling and colleagues (2005) designed a study to assess the risk of steroid immunosuppression and specifically address this problem of etiologic differentiation by including a population of individuals with either giant cell arteritis or polymyalgia rheumatica. Both conditions are treated with corticosteroids early in their courses rather than after a protracted pattern of chronic inflammation. The investigators found that with one to three years of moderate to high-dose steroids, there was no increased risk of lymphoma in this population. Instead, they found a statistically significant reduction in the rate of lymphomas. While these findings cannot be extrapolated to other immunosuppressive agents whose mechanism of action is different from that of corticosteroids, this study suggests that inflammation may have a greater role in lymphomagenesis than treatment with some immunosuppressive agents.

Acquired Immunodeficiency

NHL is one of the most common malignancies associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and rates of HL are also elevated among those infected with HIV. As early as 1985, NHL was recognized as an AIDS-defining illness when approximately 4% of all AIDS cases first presented with lymphoma. Although HIV is not considered to be an oncogenic virus, it contributes to lymphomagenesis by impairment of cell-mediated immunity and increased opportunity for virally induced cell proliferation, leading to an accumulation of genetic lesions. About 50% of HIV-associated lymphomas are EBV-positive. Burkitt lymphoma and centroblastic lymphoma are associated with EBV in 30% and 40% of HIV-positive cases, respectively, unrelated to the severity of immunodeficiency. In contrast, immunoblastic lymphoma, primary central nervous system lymphoma, and primary effusion lymphoma are almost always EBV-associated and usually occur only in strongly immunosuppressed AIDS patients. This variability suggests other factors must also be involved in the etiology of AIDS-related lymphomas. Although incidence of NHL in HIV-positive individuals has decreased since the mid-1990s, NHL still accounts for about 20% of all AIDS-related deaths in countries having broad access to HAART. The findings by Biggar and colleagues (2006) that show an increasing excess of HL among persons with AIDS are perplexing. These investigators speculate that in severely immunosuppressed individuals with AIDS, Reed-Sternberg cells are incapable of producing the cytokines required to perpetuate survival; however, in the presence of the immune-modulating effects of antiretroviral therapy, these malignant cells are able to establish a microenvironment that facilitates their own proliferation and expansion, with the ultimate development of HL.

Infectious Agents

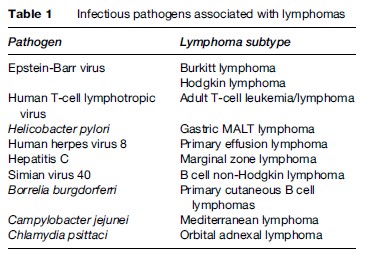

The number of viruses and bacteria that have been associated with lymphoma is steadily increasing (Table 1).

These infections increase the risk of lymphoma through numerous mechanisms, including immunosuppression, direct oncogenic mutation of cellular DNA, and chronic antigenic stimulation. Each infectious agent is briefly discussed below.

Epstein-Barr Virus

Epstein-Barr virus is a ubiquitous virus that persistently infects more than 90% of adults in developed countries and essentially all individuals living in developing countries. Although primary infection is usually subclinical in nature, the virus remains latent in memory B cells. EBV is associated with infectious mononucleosis, and viral DNA and proteins are found in lymphoma cells. EBV has been shown to be capable of B-cell activation, which could lead to a genetic mutation occurring in a virally infected B lymphocyte. Many lymphomas arising in the setting of immunosuppression are EBV-associated, including those found in recipients of organ transplantation and those associated with HIV. These most likely represent reactivation of latent EBV infection. EBV is also associated with approximately 30–40% of Hodgkin lymphomas, most aggressive natural killer (NK) cell lymphomas and leukemias, a subset of peripheral T cell lymphomas, and virtually all Burkitt lymphomas arising in malarial areas.

In developed countries, approximately 40% of HL are EBV-positive. The role of delayed EBV infection, characterized by development of infectious mononucleosis in adolescence, has been examined but not confirmed as a risk factor for HD. Risk has been estimated to be 2.5 and lasts up to 20 years after initial infection, suggesting a link with EBV or confounding due to socioeconomic class and late exposure to infections or to hyperreactivity resulting from antigenic stimuli.

The onset of endemic Burkitt lymphoma is characterized by high EBV antibody titers. The relative restriction of endemic Burkitt lymphoma to the wet, temperate lowlands of Africa and New Guinea suggests an etiologic significance of the convergence of two pathogens: Plasmodium falciparum in endemic malarial infestation regions, and EBV reactivation among malarial-infected children. Only about 15–25% of Burkitt lymphoma cases in nonendemic areas are associated with EBV