The WHO (2004) reported that the 2004 annual maternal mortality worldwide was 529 000, 99% of which occurred in developing countries. The lifetime risk of dying from pregnancy-related causes for a woman living in resourcepoor countries is 1 in 48, in sharp contrast to developed nations, where the risk is only 1 in 1800.

Before the start of the twentieth century, the overall maternal mortality rates worldwide were similar. By about 1900, maternal mortality in Europe and North America had started a gradual decline, mainly as a result of improvements in sanitation and living conditions, although it showed quite a lot of variation between countries even within the developed world. In 1900 the maternal mortality rates were the lowest in Sweden and northern Europe (approximately 200 deaths/100 000 live births). The MMR in England and Wales at that time was twice that of Sweden but half that of the United States, which had an MMR of about 700. In the 1930s, a sharp decline occurred in maternal mortality in most developed countries, bringing rates down to the very low level of fewer than 100 deaths/100 000 live births all over Europe and in the United States. A number of interventions have been implicated in causing this decline – not least of which were the introduction of antibiotics and ergometrine, skilled attendance at delivery, and access to emergency obstetric care. These interventions resulted practically in the elimination of maternal deaths due to sepsis and hemorrhage, such that there was a shift in the burden of cause-specific mortality.

The picture in the developing countries, however, is still very different. Very little historical data are available and even recent studies conducted in these countries rarely collect information on the causes of death in a standard format or use a standard classification system as in the ICD coding. Efforts to collect country-specific data on maternal mortality were only attempted in the 1990s, and even then these efforts were largely based on modeling.

Maternal deaths may be classified as:

- Direct, that is, maternal death occurs as a result of a complication of pregnancy, labor, or puerperium.

- Indirect, that is, death occurs as a consequence of preexisting disease or diseases that developed during pregnancy but not directly as a result of the pregnancy itself.

Direct Causes Of Maternal Death

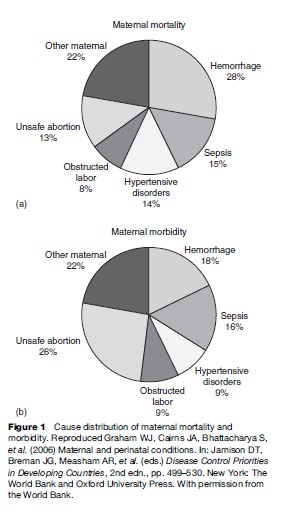

In developing countries, almost 80% of all maternal deaths occur as a result of a direct obstetric complication. Figure 1 shows maternal mortality from different obstetric causes. Where maternal mortality is high, the causes of death are similar, although the absolute levels and the proportion of death due to specific causes vary from region to region. The five main direct causes of death are relatively unvarying.

Hemorrhage

Hemorrhage or bleeding may occur antepartum, intrapartum, or postpartum and is one of the leading causes of death, especially if it occurs in the postpartum period. It is estimated that death may occur within two hours if a massive uterine bleeding, usually due to failure of the uterus to contract, is not managed immediately. The risk factors for intrapartum or postpartum hemorrhage include history of bleeding in a previous pregnancy, previous cesarean section, multiple pregnancies or polyhydramnios, placenta previa, and prolonged labor. Anemia increases the risk of dying from a hemorrhage by reducing a woman’s hematological reserve.

Genital Tract Sepsis

Puerperal sepsis is said to occur when two or more of the following conditions are present in a woman following delivery: fever, pelvic pain, abnormal or foul-smelling vaginal discharge, or delay in the reduction of the size of the uterus. Historical data indicate that in most cases puerperal sepsis is related to infection contracted during labor, and the risk of infection increases with the number of vaginal examinations. Other factors that play a role in causing intrapartum or postpartum sepsis are prolonged labor with early rupture of membranes and unhygienic birthing conditions. Sexually transmitted diseases, especially HIV infection, are associated with a higher incidence of sepsis and increased case fatality rates.

Hypertensive Disorders Of Pregnancy

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy include pre-eclampsia and eclampsia and are defined as raised blood pressure and proteinuria with or without edema; in eclampsia convulsions also occur. Although hypertensive disorders may account for fewer deaths than hemorrhage or sepsis, the absolute risk of maternal deaths from the condition is elevated in areas with high maternal mortality rates. This is because the overall incidence of hypertension is high and a high case fatality rate is associated with it. Several risk factors have been identified for hypertensive disorders, including multiple pregnancy and primiparity.

Obstructed Labor

Obstructed labor usually results from cephalo-pelvic disproportion or malpresentation. When delivery care is poor or delayed, obstructed labor frequently results in maternal or perinatal mortality or morbidity. Short stature and malnutrition in childhood predispose girls to obstructed labor later in life. A 1995 meta-analysis by WHO suggested a 60% greater likelihood of obstructed labor among women in the lowest quartile of height, compared with the highest quartile. Maternal death occurs mostly from a ruptured uterus or from massive hemorrhage and/or sepsis. Perinatal death occurs almost invariably as a consequence of obstructed labor unless cesarean section delivery is undertaken. One of the other serious maternal conditions that may occur as a result of obstructed labor is an obstetric fistula. A fistula causes fecal or urinary incontinence and can make life for a woman suffering from it seem worse than death due to social ostracism.

Unsafe Abortion

Unsafe abortion accounts for a significant proportion of maternal deaths. The risk of death varies significantly between world regions, however, from 1 death per 1900 induced abortions in Europe to 1 in 150 in Africa. Unsafe abortions lead to death through incomplete abortion, sepsis, hemorrhage, genital and abdominal trauma, perforated uterus, or poisoning from abortifacient medicines. Unwanted pregnancies, absence of legal contraception, and pregnancy termination services predispose women to unsafe abortions by unskilled attendants.

Indirect Causes Of Maternal Death

The two most important indirect causes of maternal death in the developing world are anemia and infection.

Anemia

Anemia is probably the most prevalent indirect cause of maternal mortality and severe morbidity in resourcepoor countries. Anemia occurs physiologically in pregnancy due to hemodilution, and when this is superimposed on the chronic condition caused by nutritional deficiency and infection, it can give rise to severe anemia of pregnancy, with hemoglobin of less than 7 g/dl. As a result, heart failure may occur during pregnancy or labor. Anemia also increases the risk of death from intrapartum or postpartum bleeding or sepsis. There is clear evidence to suggest that women with severe anemia run a risk of dying in pregnancy and childbirth which is 3 to 5 times greater than that of women without anemia.

Infection

The cell-mediated immune response is dampened in pregnancy and thereby makes the pregnant woman more susceptible to infections such as tuberculosis and malaria. Moreover, the severity of the infections is also increased in pregnancy and results in a corresponding increase in risk of dying from the condition. Other important infections in pregnancy include viral hepatitis and AIDS.

Sociodemographic Determinants Of Maternal Health

The sociology of pregnancy and giving birth is culture specific but influences maternal health to no less a degree than the medical conditions. Some of the sociodemographic factors are obvious, such as age at first pregnancy or contraceptive behavior, whereas others such as lifestyle and cultural factors exert a covert influence.

- Age: Extremes of age pose risks for the health of the mother, not only in physical terms, but also in terms of psychosocial well-being. This effect is more prominent in primigravid women. Although ages 15 to 49 years are generally accepted as within childbearing age, teenage pregnancy is a problem in both developed and developing societies. In recent times, assisted reproductive technology and lifestyle choices have meant that more women are postponing pregnancy either voluntarily or involuntarily to an older age. This is not without health and social implications for the mother as well as the baby.

- Birth spacing: A technical consultation meeting organized by WHO recommends a minimum interval of 24 months after a live birth and at least 6 months after a miscarriage or termination before the next pregnancy in order to minimize maternal and perinatal risks. This recommendation should, however, be assessed in light of maternal age, parity, previous obstetric history, and family aspirations.

- Substance misuse in pregnancy: Smoking while pregnant has detrimental effects on the baby. Smoking in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy can result in miscarriage or preterm delivery and accounts for up to 25% of low-birth-weight infants. Smoking has also been implicated as a cause of cot or crib death. With regard to alcohol, most of the evidence comes from the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 6.7 births per 10 000 live births result in fetal alcohol syndrome. At the less extreme end, moderate to high alcohol consumption can cause miscarriage, preterm birth, and growth restriction of the baby.

- Nutrition in pregnancy: Both under and overnutrition of the mother affect the baby adversely. Severe proteincalorie malnutrition and micronutrient deficiency can result in preterm delivery and a growth-restricted baby, whereas overnutrition and maternal obesity are associated with preeclampsia, diabetes, increased operative deliveries, and stillbirth.

Organization Of Maternal Health Care

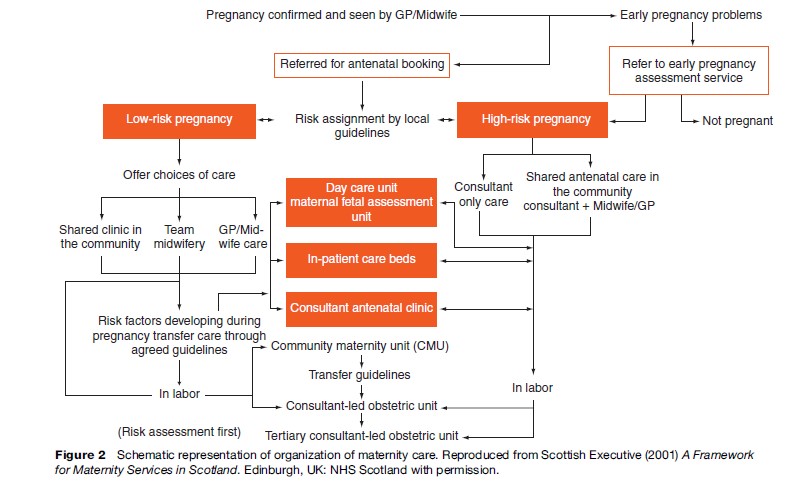

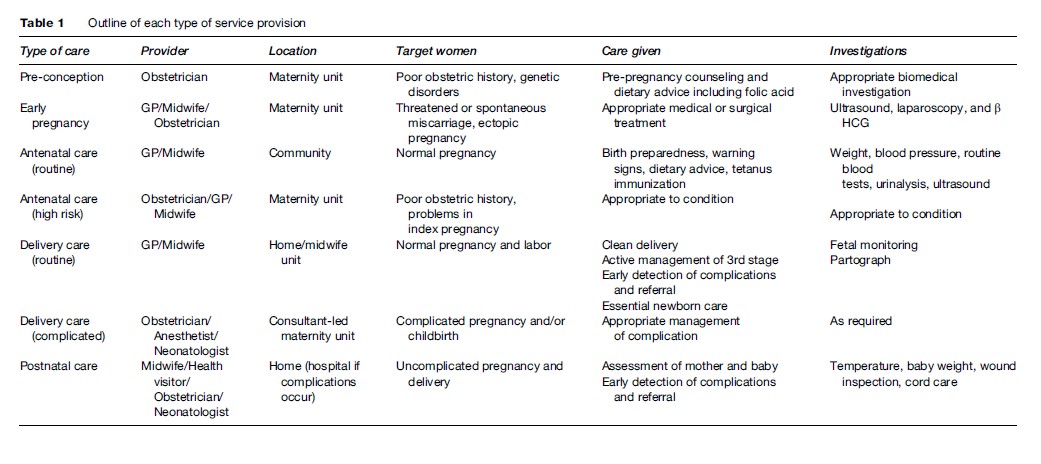

Figure 2 shows a schematic representation of how maternal health care should be organized. Structurally the care is organized into separate but interrelated groups according to the time of pregnancy (Table 1).

Prepregnancy And Early Pregnancy Services

Good health before and during early pregnancy benefits the mother, the baby, and the wider family. Every woman should have access to prepregnancy counseling and advice regarding smoking cessation, alcohol consumption, and dietary advice, including folic acid consumption to prevent neural tube defects in the baby. Moreover, women with poor obstetric history, medical problems, and family history of relevant serious illness benefit from early pregnancy services. Early pregnancy service also deals with any untoward symptoms such as bleeding and abdominal pain and arranges appropriate investigations and treatment. The provider of this service varies according to the severity of the situation. Routine prepregnancy and early pregnancy services can be delivered at the community level by a midwife or a general practitioner (GP); high-risk or symptomatic cases need to be managed at specialist centers with appropriate management facilities.

Antenatal Care

Maternity services should provide a woman a family centered, locally accessible, midwife-managed, comprehensive and effective model of care during pregnancy with clear evidence of cooperation between primary, secondary, and tertiary services. This is the basis of provision of antenatal care (ANC). Antenatal clinics were started between 1915 and 1920 in the United States, Australia, and Scotland to screen healthy pregnant women for signs of disease. In recent times, the emphasis has shifted from provision of antenatal care to provision of obstetric care at delivery in order to prevent maternal morbidity and mortality. This is because of the paradigm shift from the at-risk approach to treating every pregnancy as possible high-risk. However, ANC is still considered to be of benefit, especially to the baby, for early detection of pregnancy complications and for preparing women for delivery. A recent multicenter trial (Villar et al., 2001) conducted by WHO highlighted that routine antenatal care can be delivered by no more than four visits to the clinic. Based on a systematic review of different models, WHO recommend the following content for routine antenatal care:

- History taking of previous obstetric events, complaints in index pregnancy, and any relevant previous medical history;

- Clinical examination, height and weight, blood pressure;

- Obstetric examination for gestational age estimation, fetal heart, determination of presentation and position;

- Gynecological examination;

- Urine test (multiple dipstick);

- Laboratory investigations: hemoglobin, blood group and Rh status, syphilis and any other symptomatic sexually transmitted infection;

- Advice on emergencies, birth preparedness, delivery, and lactation;

- Education about clean delivery and recognizing warning signs;

- Iron and folic acid supplementation;

- Tetanus toxoid immunization.

Although this content forms the basic package for routine antenatal care, several other interventions are often delivered from the antenatal clinics that are relevant to the consumer population. Voluntary HIV testing and counseling, screening and treatment of syphilis, and antenatal screening for congenital abnormalities are some interventions commonly delivered during the antenatal period.

In addition to routine antenatal care, maternal health services also manage any complications occurring in the antenatal period; often at a higher referral level. This constitutes evidence-based management of antepartum hemorrhage, pregnancy-induced hypertension, preterm labor, growth-retarded baby, and any other pregnancy-related complication.

It has to be remembered, however, that antenatal care is effective in improving the health of the mother and the baby and in preventing perinatal deaths, but it has a limited role in preventing maternal mortality.

Delivery Care

As with antenatal care, delivery care is provided at two levels. At the community level, routine delivery care is given to all women having uncomplicated pregnancies and deliveries; referral to a higher-care center is sought at the first sign of any complication. The challenges of delivery care in developing countries center around the safety of childbirth, whereas in countries where safety is accepted as the norm, the issues are more around choice and giving every woman the right to choose how and where they give birth.

Basic delivery care consists of the following:

- Clean birthing technique;

- Active management of the third stage of labor;

- Early cord clamping;

- Controlled cord traction;

- Oxytocics on the birth of the anterior shoulder;

- Essential newborn care.

In addition to this, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) also recommend that the following elements be available at the primary level of care:

- Parenteral antibiotics;

- Parenteral oxytocic drugs;

- Parenteral sedatives/anti-convulsants (e.g. magnesium sulphate) for pre-eclampsia/eclampsia;

- Facilities for vacuum or forceps delivery;

- Facilities for manual removal of placenta;

- Facilities for removal of retained products of conception.

These elements form what is termed ‘basic essential obstetric care.’ Over and above these, the services constitute ‘comprehensive essential obstetric care,’ usually delivered at a district hospital level, if facilities are available for:

- Cesarean section;

- Blood transfusion.

At the tertiary level, consultant-led maternity units providing a full range of services to women with high-risk pregnancies should have available:

- Obstetric/midwifery specialist services;

- Anesthetic services and access to adult intensive care;

- Neonatal resuscitation facilities and access to neonatal intensive care;

- Round-the-clock radiology and imaging;

- Round-the-clock laboratory facilities;

- Blood transfusion.

It is also recommended that maternity services have a holistic approach providing a fully integrated childbirth service tailored to the individual needs of women, preferably with continuity of care.