Monopoly is a market situation in which there is only one seller of a product. The product has no close substitutes. The cross elasticity of demand with every other product is very low. The monopolized product must be quite distinct from the other products so that neither price nor output of any other seller can perceptibly affect its price-output policy. ‘Inter alia’ it implies that the monopolist cannot influence the price-output policies of other firms. Thus he faces the industry demand curve, his firm being an industry itself.

The demand curve for his product is, therefore, relatively stable and slopes downward to the right, given the tastes and incomes of his customers. He is a price-maker who can set the price to his maximum advantage. However, it does not mean that he can set both price and output. He can do either of the two things.

His price is determined by his demand curve, once he selects his output level. Or, once he sets the price for his product, his output is determined by what consumers will take at that price. In any situation, the ultimate aim of the monopolist is to have maximum profits.

The type of monopoly described above is simple or imperfect monopoly. There is also pure, perfect or absolute monopoly to which we refer now. But we shall be concerned mainly with detailed discussion of simple monopoly and discriminating monopoly.

In pure monopoly one firm produces and sells a product which has no substitutes. The cross elasticity of demand with every other product is zero. In Triffins words, “Pure monopoly is that where the cross-elasticity of demand of the monopolist’s product is Zero.” The monopolist has absolutely no rivals. His price-output policy does not influence firms in other industries. Nor is he affected by others.

Pure monopoly “occurs when a producer is so producer is so powerful that he is always able to take the whole of all consumers’ incomes whatever the level of his output. This will happen when the average revenue curve for the monopolist’s firm has unitary elasticity (is a rectangular hyperbola) and is at such a level that all consumers spend all their income on the firm’s product whatever its price.

Since the elasticity of the firm’s average revenue curve is equal to one, total outlay on the firm’s product will be the same at every price. The pure monopolist takes all consumers’ incomes all the time.”

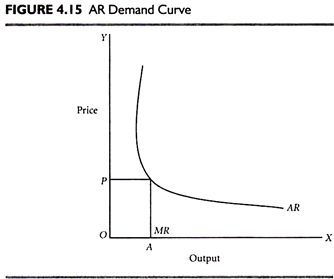

In Fig. 4.15, AR is the demand curve facing the pure monopolist. Since AR is a rectangular hyperbola, MR coincides with the X-axis. The monopolist can fix either price or output. If he fixes OP price, then the level of output OA to be sold is determined by his customers. If he fixes his output at OA, then price OP to be paid for that is also decided by the customers. Thus even a pure monopolist with no rivals at all cannot fix both price and output at the same time.

Since a pure monopolist earns the whole income of the community all the time, he will maximize his profits when his total costs are the lowest. It implies that his profits are the maximum when he sells a very small output, only one unit at a very high price and in the process takes away the entire income of consumers. This is, however, not possible. So, pure monopoly is only a theoretical Possibility. It has never existed and will never exist. We, therefore, pass on to the study of price-output policies under simple or imperfect monopoly.

Bilateral monopoly refers to a market situation in which a single producer faces a single buyer. The seller considers himself a monopolist. So does the buyer. The problem of bilateral monopoly has two facts. The first refers to isolated exchange between two individuals completely cut off from other people.

“Price formation in the case of isolated exchange”, as stated by Edge worth, “is essentially an indeterminate problem, which is not soluble because there is an undecidable opposition of interests as each aims at the maximization of his money gain.” The second relates to the case of a single producer selling a raw material product to a single buyer who is also a monopolist in selling the finished product. Cournot offered a determinate solution to this case.

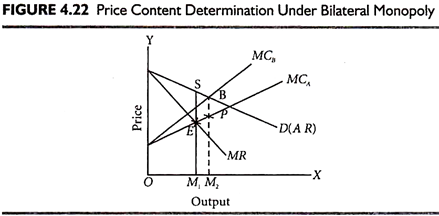

Suppose A is the single producer of bauxite, who sells it to B, who manufactures aluminium and sells it in a monopoly market. In Fig. 4.22 D is the market demand curve of B, the single buyer. D and MR are, therefore, the demand and marginal revenue curves of A, the single seller. MCa is the marginal cost curve of the single seller A which cuts the MR curve at E. The seller monopolist would like to sell OM1 output at M1S price in order to maximize his profits.

It is assumed that A regards B as one of the many buyers in a competitive market. Similarly B considers A as a competitive seller. It implies that each acts autonomously so that the MCA curve is both the marginal cost curve and the supply curve.

To maximize his profits the buyer monopolist will have a curve MCB marginal to the MCA curve to meet his demand curve D at B. He would thus be prepared to pay M2P price for OM2 quantity. The price M2p is determined by the equality of B’s marginal cost with A’s potential supply curve MCA. It leads to clash of interest because the monopoly buyer wishes to pay less price (M2P < M1S) and demands more quantity (OM2 > OM1) than what the seller monopolist is prepared to accept an offer. Thus, price and quantity are indeterminate.

Cournot, however, offered a determinate solution to this problem. According to him both the seller and the buyer monopolists would accept and pay M1S price for OM1 output because it is at this level that they maximize their profits; the seller monopolist from the buyer monopolist and the buyer monopolist from the purchasers of the finished product aluminum.

But Cournot’s solution is not regarded as correct, for the buyer monopolist possesses dual monopoly. On the one hand, he has the monopoly of buying bauxite and on the other, of selling aluminium. He would, therefore, try to extract monopoly profit from two sides. Naturally, his intention would be to pay a low price M2P and buy a larger quantity OM2 of bauxite.

The seller monopolist on his part would wish to sell a smaller quantity OM1 at a higher price OM2. The price-quantity situation is thus indeterminate and will lie somewhere between M1S and M2P price and OM1 and OM2 quantity. Indeterminacy does not imply that there is no equilibrium position and no trade takes place. Rather it means that the determinate solution to the problem of bilateral monopoly is beyond the tools of economic analysis.