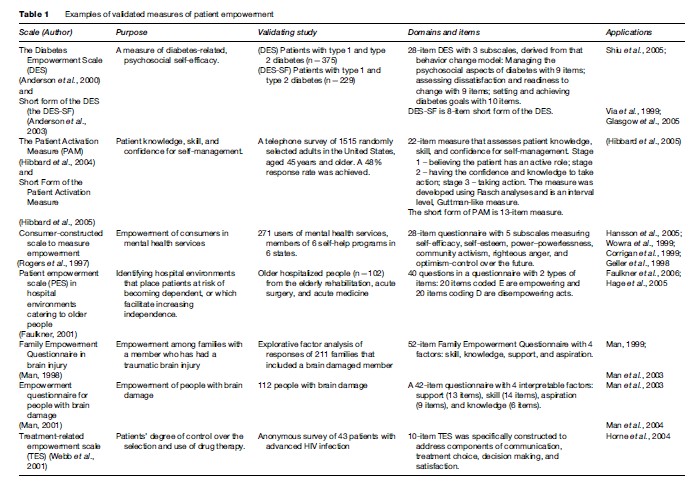

A recent review of the English language medical literature between 1980 and 2005, summarized in Figure 1, found a range of applications of empowerment principles in health care (Loukanova and Bridges, 2008). First, following more general social and political empowerment movements, 26% of all English language articles in the medical literature on empowerment have focused on issues of social empowerment, which relate to issues such as discrimination and health disparities. Second, research concerning nurse empowerment has been a major topic in health care, accounting for 16% of the literature. This body of work focuses on expanding nursing education, developing leadership and management skills, and fostering greater professional autonomy and job satisfaction. It also relates to the imbalances in professional power in the health-care workplace. Third, studies concerning the empowerment of organizations accounted for 10% of the literature. These papers have addressed issues such as improving staff performance, organizational culture, and the overall quality of the organization. Interestingly, there was very little research concerning the empowerment of physicians (only 4% of the literature). These articles focused on physicians’ need for power to fulfill and manage their professional responsibilities to achieve outcomes of improved work efficiency, patient satisfaction, and physician self-governance.

The most prominent topic in the literature on empowerment in health focused on patient empowerment, accounting for 44%, and while we touch briefly on other types of empowerment in this research paper, we focus primarily on issues related to patient empowerment. The promotion of patient empowerment is dependent upon changing both patients and the health-care system. While patient empowerment can be established by introducing more choice for patients it also requires a system that is more patient centered to facilitate such choice.

Empowerment As An Idea

At the core of the concept of empowerment is the idea of physical or legal power. The word power comes from the Latin word potere, which means ‘to be able’ or to have the ability to choose. The verb empower means ‘to give authority or power to; to authorize or give strength and confidence to.’ In terms of its general use, Webster’s dictionary defines power from a different perspective, citing the ‘ability to act or produce an effect.’ The concept of empowerment, however one defines it, seems to transcend its dictionary definition, representing a complex concept with a long and illustrious history. From an economic perspective, the roots of empowerment can be found during the Industrial Revolution in the late eighteenth century. The concentration of wealth in the ownership class was thrown into sharp relief by the effects of rapid industrialization and its effect on the class system. Empowerment evolved from the notion of increasing worker motivation and improving managerial leadership to the processes of giving subordinates greater resources and discretion today. Empowerment in the workplace is underpinned by Kanter’s structural theory of organizational behavior (1993), which states that the empowerment of staff is important to overall work effectiveness and job satisfaction.

In the twentieth century, empowerment became associated with the struggle of those who held the least power in society. This was especially true for minority groups, who were discriminated against on the basis of their religion, gender, or race, perhaps best illustrated by the Civil Rights movement in the United States. Since the 1970s, empowerment has also served as the basis for defending community interests and promoting the mutual participation relationship between doctors and patients in the context of the consumer movement. And today, empowerment has a broader meaning, which focuses on types of self-realization and mobilizing the self-help efforts of people, rather than simply providing them with social welfare.

Empowerment In Medicine And Health

For most in medicine the thought of power is often focused on issues of control and domination. Focusing only on these aspects of power, however, limits our understanding of empowerment as it relates to any application in society. That said, the modern interpretation of power is extremely varied, and has to be considered in light of its use in technology, physics, mathematics, statistics, religion, politics, feminism, civil rights, psychology, disability, and even medicine. Taking this into account, the power element of empowerment has the potential for extremely broad interpretations, and as such could be applied to a broad range of stakeholders in health care. Early empowerment movements in health focused on services for and attitudes toward people with disabilities and mental illness, incorporating both community action and national/state legislation aimed at preventing discrimination. In more recent years, empowerment has hit the mainstream – being the focus of national attention and debate for a broader patient population.

Zimmerman (1990, 1995) and Rappaport (1984, 1987) are two of the leading researchers in the development of empowerment theory in health care. Zimmerman (1990) conceptualized empowerment at three different levels: (1) psychological empowerment is empowerment at the individual level of analysis; (2) organizational empowerment represents improved effectiveness resulting from organizations successfully competing for resources, networking with other organizations, or expanding their influence; and (3) empowerment, at the community level, refers to individuals working together in an organized fashion to improve their lives collectively and create links among community organizations and agencies that help maintain quality of life. Zimmerman (1995) expanded on his theory by distinguishing between processes and outcomes. Empowering processes refer to how people, organizations, and communities become empowered, whereas empowered outcomes refer to the consequences of those processes. He argues that empowerment can take many different forms and is dependent on the context for which it is being defined.

Rappaport (1984) takes a more pragmatic approach, noting that empowerment is easier to define in its absence – that is, through the eyes of the unempowered. Rappaport argues that it is simpler to identify the powerless, and significantly more difficult to define empowerment positively. He argues that the empowerment concept provides a useful, general guide for developing preventive interventions in which the participants feel they have an important stake. He also argues that empowerment should be adopted as a guiding principle for community psychology (Rappaport, 1987).

Despite the challenges in defining empowerment in positive terms, it does have a tremendously positive connotation, belonging to a class of similar positive constructs that have emerged in the past 20 years (e.g., patient activation, self-efficacy, shared decision making, patient autonomy). Empowerment has been employed universally in the medical literature as a positive construct independent of the area of its application. Interest in empowerment in medicine now transcends its initial application in the psychology literature (Rappaport, 1984) to includes issues of organizational and clinical management (Loukanova et al., 2007). Empowerment has become an important concept in understanding individual-, organization-, and community-level development in health care, although a widely accepted definition of empowerment still remains elusive (Gibson, 1991).

Patient Empowerment

Medicine’s tradition of physician paternalism, in which physicians control much of the information and decision making, is currently giving way to one in which patients play a significant role in medical decision making in particular and their own health care in general. Concurrent with this trend have been continued calls for medicine to embrace patient-centered care and to better inform the patient, pay more attention to patientreported outcomes including patient preferences, and to focus more on patient satisfaction. In both academic and policy circles there has also be a great deal of interest in patient empowerment, which can be considered an umbrella term, encapsulating a vast array of processes and outcomes.

Exact definitions of patient empowerment vary, depending on the disciplinary backgrounds of scholars as well the target populations of interest. In the context of nursing practice and education, Gibson defines empowerment ‘‘as a social process of recognizing, promoting and enhancing people’s abilities to meet their own personal needs, solve their own problems and mobilize the necessary resources to feel in control of their own lives’’ (1991: 359). In their research with people with mental illness, Linhorst et al. define patient empowerment as ‘‘having decision-making power, a range of options from which to choose, and access to information’’ (2002: 472). According to Chamberlin (1997: 43), the key elements of empowerment in mental health are ‘‘access to information, ability to make choices, assertiveness and self-esteem.’’ In relation to health information, empowerment means that patients are able to take control of their own health care and to make informed decisions. In parallel literature, the term activated patient has also been used to refer to patients who actively participate in their health care through knowledge of disease and treatment options and acquisition of skills to manage their health status (Hibbard et al., 2004).

Types Of Patient Empowerment

The patient empowerment literature has focused on society in various ways, with subliteratures centered around individuals, families, or communities. Articles on individual patient empowerment focus on the relationship between the individual who receives medical attention and the health-care system, while articles on family empowerment take a broader perspective of care, involving other caregivers such as parents or spouses. Community empowerment encompasses a group of people living in the same locality, sharing a common disease, sharing ethnic or cultural characteristics, and taking action to improve their lives and to achieve greater equality of power (Figure 2).

Models Of Empowerment

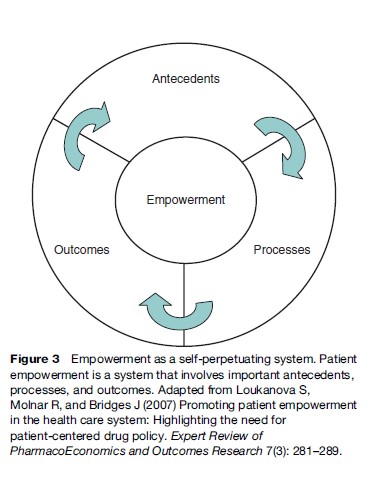

Existing conceptual models in the literature involve issues such as community empowerment (Menon, 2002), nursing empowerment (Gibson et al., 1991), or family empowerment. Population or disease-specific models have been published in the area of mental illness, brain damage (Man et al., 2003), trauma patients (Fallot et al., 2002), and diabetes (Anderson et al., 2000). In a recent review of the literature, Loukanova et al. (2007) presented a conceptual model of empowerment for application to a general patient population. Here, empowerment is understood as a continually evolving process based on antecedents, or the necessary elements that allow patients to start the empowerment process; processes that emphasize the interaction between patients and the health-care system; and outcomes for the individual patient. This model tries to identify what is common about the patient empowerment process across different patient groups. It is presented (Figure 3) as a cycle, based on the type of relationships between the elements and the concept of a continuum with which this process is characterized.

Antecedents to empowerment include knowledge, health literacy, patient initiative, and advocacy and access to services. Important processes of empowerment are information sharing, doctor-patient communication, choice, and shared decision making. Finally, patient empowerment aims not only to improve health outcomes, but to generate patient-centered care that will affect patient satisfaction, self-efficacy, and adherence.

Measuring Empowerment

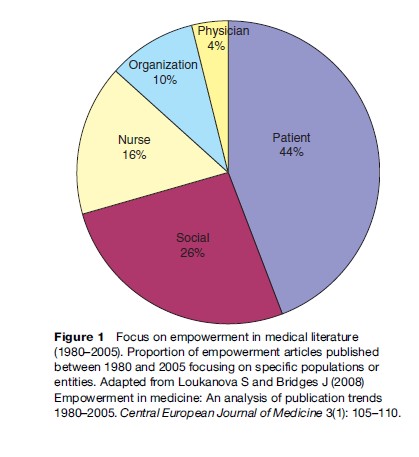

There are a number of instruments presented in the literature that attempt to measure patient empowerment, but they often focus on specific populations or diseases,

rather than the general population. Examples include the Family Empowerment Questionnaire (Man et al., 2003); the consumer-constructed scale in mental health services (Rogers et al., 1997); Diabetes Empowerment Scale (Anderson et al., 2000); Patient Activation Measurement (Hibbard et al., 2004), and the Therapeutic Alliance Scale (Kim et al., 2001) (Table 1). More research is needed to define in general the characteristics of the empowerment process that can serve as a basis for the development of a measure of patient empowerment in the general population.