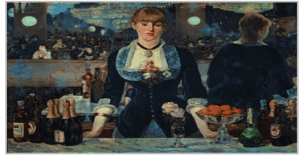

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) by Edouard Manet

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) by Edouard Manet

This Edouard Manet sculpture was displayed at the Paris Salon in 1882. It exemplifies a bar of Folies-Bergere, illustrating the scene at the Folies-Bergere nightclub (Harland et al., 2014). From a critical view, there is a vital issue that the customer and the barmaid were involved in a visual trick conversation, which originates from the supposition that the man standing to the left-hand side of the artist is showing his back and not looking at the painter face-to-face. Prudently, a viewer should stand to the right side and next to the bar instead of the back and left view, seemingly a weird depiction that drifts from the common dominant viewpoint employed when observing any painting (Collin, 2016). Besides, this artwork reveals the idea of moral dissipation. The female illustrated in the image is Suzan, a worker at the nightclub Manet represents in his workspace. Further, the orange dish suggests she is a prostitute because Manet links oranges with prostitution. As such, the club was an abode for purchasing drinks accompanied by other products of choice, which seemingly, I think, was encouraging societal decadence.

Judith Beheading Holofernes’s (1598-1602) by Caravaggio.

This is Judith Beheading Holofernes’s artwork painted between 1598-1599cc. The painting represents a true event drawn by Caravaggio, where Judith lured General Holofernes and proceeded to behead him in his tent. This artwork is currently at Galleria National d’Arte Antica in Rome. Most importantly, Judith’s deuterocanonical books recount how she worked for the public by pleasuring and seducing Holofernes, Syria’s General, by making him drunk, then slipping her weapon and killing him (Estes, 2013).

From this painting, a point of view can originate from the moment of the dramatic act of deception because this event happens on a superficial platform with a pitch-black setting. Judith’s house cleaner, Abram, is upended right next to her boss as she stretches her arm and holds a sword on Holofernes neck while lying on his belly, and the head is twisted upward, facing the killer as he is in a helpless situation. While viewing closely, Caravaggio intentionally adjusted Holofernes’s head to cut it from the body and carefully shift it to the right. Remarkably, the faces of the three characters in the story demonstrate the artist’s mastery of emotions, particularly Judith’s facial expressions showing a mixture of both determination and hatred. Moreover, this painting plays a vital role in persuading other artists like Gentileschi Artemisia, primarily outshined by Caravaggio’s practicality. Most importantly, the entire scene, especially the decapitation and blood, are claimed to have arisen from Caravaggio’s observing Beatrice Cenci’s public execution that occurred some years back. Hence, this is an epic piece because the woman liberates her society from General Holoferness’s oppressive regime.

The Blessed Virgin Mary holding dead Jesus Christ’s body (1499) by Michelangelo La Pieta

The image presents Virgin Mary holding Jesus’s lifeless body just a few minutes after the crucifixion, downfall, and removal from the cross before succeeding to the tomb. This sculpture pictures key events in Mary’s life, forming part of Mary’s seven sorrows, a catholic church prayer theme. Looking at this painting closely, Mary’s physique looks a little bigger than that of Jesus, which means the artist did this intentionally because it was prudent for Mary to support Christ’s dead body. On normal grounds, suppose the bodies of Mary and Jesus were made of similar sizes, the picture would look weird, and it would be challenging to portray Mary gracefully holding Christ’s body on her lap (Bernardini et al., 2012). The Virgin Mary presented in the painting looks very young for a mother of a 33-year-old son. Surprisingly, the painter disapproved of these claims, arguing that they could preserve their age and beauty much gentler than men. In addition, Mary looks shuttered by the dealing that resulted in her son’s death but peacefully accepts the reality as God’s will. Jesus, who is held, appears to be peacefully sleeping, characterizing the end of bloody suffering and torture he had to endure for human sake.

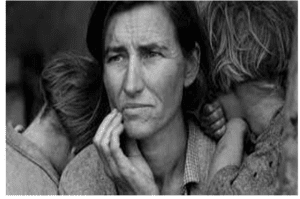

Migrant Mother (1936) Dorothea Lange.

This is a piece of art photographed by Dorothea Lange in 1936. It represents a migrant mother depicting unending bravery and poverty (Curtis, 2016). The photographer, an architect working with the Farm Security Administration, took this photograph while returning from a field trip. The woman portrayed in this picture had seven children with no job to provide for this family and primarily depended on wild birds caught by her kids as their source of nourishment. This woman looks vulnerable, disappointed, hurt, and in anguish, not knowing how to raise her kids in a place where she cannot find any job.

The woman faced the dangers of hunger. She had sold car tires and, as a result, could not seek work elsewhere. Curtis (2016) says that the woman’s facial expression, as presented in this photograph, arouses feelings of anxiety, exhaustion, and fear of unknown hopes. In my view, this picture summarizes the adversities that people experienced and how challenging it was to survive during the Great Depression. All this was typically presented with this woman’s face. Nonetheless, this picture is more focused on hopelessness and fear and does not typically demonstrate the courage displayed by the woman for the sake of her children.

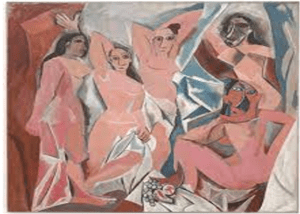

Les Demoiselles Avignon (1907) by Pablo Picasso

This Les Demoiselles Avignon artwork demonstrated a grand deviation from conventional perception and creation of artwork. The painting presents five naked women in flat-shattered pictorials, and their faces are blended with African masks (Picasso, 2013). This picture represents the popular Barcelona street known for brothels. Therefore, these five women are prostitutes apparently in a brothel, as two of them are depicted pushing curtains toward the place where the others are making sexy and seductive poses. The painter of this painting, Picasso, assumed that the African masks on the faces of the people on the right were to protect them from evil spirits. Nonetheless, from the painter’s viewpoint, the greatest danger while making this portrait was the deadly sexual diseases that caused much anguish in Paris. However, in my view, I am persuaded to argue that the biggest threat then was prostitution, which resulted in increased sexually transmitted diseases, which were unbearable and threatened society then.

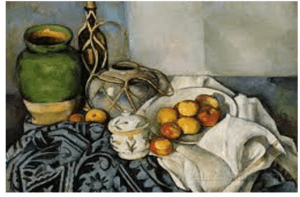

Still Life with Apples (1893-1994) by Paul Cezanne’s

This is one of Paul Cezanne’s iconic paintings of the 19th Century, known as Still Life with Apples (1893-1994). It also influenced 20th-century painters because Cezanne was popularly known for using simple objects to make very authoritative artwork (Cézanne, 1900). In this image specifically, Cezanne uses apples and fruits in his works. For the picture to look finer, Cezanne creates diagonal brush strokes on all the figures in the artwork. Furthermore, in this sculpture, Cezanne assumes that everyone knows and understands an apple and its form. As such, he dissociated his primary concern from the look of an apple to its quantity, depth, composition, structure, and color, which was much more profound than just creating what the viewer is already aware of (Massey, 2009). Despite the painting being static, the left side of the table is much different from the right. As a result, it incorporates a different viewpoint into this vague static life. Consequently, the image has diverse meanings and perspectives where one can say that still life is much prettier than imitated life. This picture teaches one to learn to realize their sensations and put their priorities right.

References

Bernardini, F., Rushmeier, H., Martin, I. M., Mittleman, J., & Taubin, G. (2012). Building a digital model of Michelangelo’s Florentine Pieta. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications, 22(1), 59-67.

Cézanne, P. (1900). Still life with apples. Budek Films & Slides.

Collins, B. R. (Ed.). (2016). Twelve Views of Manet’s Bar. Princeton University Press. Curtis, J. C. (2016).