As the UNAIDS Director Dr. Piot points out, the exceptional nature of AIDS requires an exceptional response and that includes responding to the rights of infants, children, and adolescents. Unfortunately, there is a lack of public discourse on how this pandemic has negatively affected the lives of millions of children.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) provides a cogent blueprint for how to establish national policies that are formulated with the best interests of the child in mind, that protect against discrimination, and that strive to promote a child’s right to survival. One critical principle in the UNCRC is the responsibility of individual governments and the international community to provide assistance to parents, guardians, and communities as needed. An analysis of reported funding for the 17 most affected countries in sub-Saharan Africa in 2003 found that $200–300 million was earmarked for orphans and vulnerable children due to the HIV/AIDS pandemic. In the case of U.S. funding, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) contributes 3% of its total budget (approximately $50 million) to orphans and vulnerable children programs in its 15 focus countries, with approximately half to four of the focus countries (Ethiopia, Mozambique, Uganda, and Zambia). While these efforts are laudable, they are not directed at the countries with the highest prevalence of child orphans due to AIDS. Given the tremendous financial burdens faced by countries most severely hit by HIV/AIDS, increased funding and coordinated support from the international community is absolutely essential. Monitoring is also critical so that obstacles preventing appropriate distribution to communities are overcome.

In spite of the pressing physical, mental, social, moral, and spiritual issues facing children as a consequence of AIDS, their overall care in this pandemic is woefully neglected. An initial attempt to begin to address these issues occurred at the 2001 United Nations General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS), when heads of state made a Declaration of Commitment to address the needs of orphans due to HIV/AIDS. However, in 2003, only 6 of 46 (13%) sub-Saharan African countries had a national policy on orphans and vulnerable children in place (another 20% were in the process of formulating a national policy); less than one-third of poverty reduction strategy papers and national HIV/AIDS plans mention the issue of children affected by AIDS; and only Cameroon had proposed any child-focused initiatives. Currently, less than 10% of children orphaned as a consequence of AIDS are receiving support services, mostly in the form of material, rather than psychological, support.

In March 2004, UNAIDS and collaborating organizations devised a blueprint for care, Framework for the Protection, Care, and Support of Orphans and Vulnerable Children Living with HIV and AIDS, which focuses on five areas: strengthening the capacity of families to protect and care for orphans and vulnerable children by prolonging the lives of parents and providing economic, psychosocial, and other support; mobilizing and supporting community-based responses to provide immediate and long-term support to vulnerable households; ensuring access for orphans and vulnerable children to essential services, including health care, education, and birth registration; ensuring that governments protect the most vulnerable children through improved policy and legislation and by channeling resources to communities; and raising awareness at all levels through advocacy and social mobilization to create a supportive environment for children affected by HIV/AIDS.

Strategies to assist children need to be directed upstream and downstream. The global AIDS pandemic is undermining the medical, economic, and social structures of many societies. Health systems in general are overburdened and underfinanced to care for patients with HIV/AIDS. Money that is directed to these patients is diverted from other lifesaving child health programs like immunizations and treatment for pneumonia and diarrheal infections. A basic tenet of the UNCRC is that children have a right to the highest attainable standard of health; governments are obligated to work to decrease infant and child mortality and to provide appropriate pre and postnatal care to women. Knowing that the proportion of child deaths due to HIV infection is rising, and that a child’s risk of death increases dramatically if the mother dies, it is incumbent upon governments to act accordingly. Women have the right to appropriate treatment to increase their longevity and quality of life. A secondary benefit is that healthy women will have healthy children.

Children have a right to a standard of living adequate for their physical, mental, spiritual, moral, and social development. Implicit here is the right to water, sanitation, housing, a safe home, and other basic needs. Once again, governments have a responsibility to provide for families if the families cannot make ends meet to fulfill this right. The extensive kinship network that is caring for orphaned children in Africa is to be applauded for its demonstration of true community involvement. They have put into practice the adage, ‘‘It takes a village to raise a child.’’ Nonetheless, these networks are fragile and at risk of collapsing under the burgeoning weight of having more children to provide for without the requisite support from adult wage earners and the government. Also, for cultural reasons and issues of stigma, these networks are not universally present. In response to this, successful community-based orphan visiting programs have been in place as early as 1996 in sub-Saharan Africa. Community members are trained in HIV/AIDS, stigma, discrimination, and child health and development needs and then make regular visits to children orphaned by AIDS, whether they are living with a family or in a local group home. For the few countries that have them, there is an urgent need to close national orphanages and divert the funds into such community-based centers and families caring for orphans.

For women and men who are infected or have active disease, in addition to provision of medications, a holistic approach that addresses the needs of the entire family is warranted, for example, increasing funding to make all households food-secure, to provide adequate shelter, and to make education affordable and accessible to all children. The penchant for ‘targeted’ interventions and narrow funding streams risks thwarting this approach. Also, giving only children food results in resentment and the unwanted effect of people wanting to declare relatedness to an HIV-infected person so that they receive assistance. Training people (e.g., psychologists, social workers, church and tribal leaders, as culturally appropriate) who can help facilitate discussion among family members about what it means to live with a chronic and ultimately fatal illness and can help families plan for future events (e.g., the loss of one or both parents) can improve the mental health of the household. Having people who are specially trained to work with children will address their unique needs based on their level of development.

The right to education contributes to a child’s holistic development. A school setting may be the place where most children receive necessary health education, including education about pregnancy and sexually transmitted disease prevention, which is vitally important in the era of AIDS. A study in Zimbabwe found that the most important resource requested was educational subsidies. Free, universally available, and accessible primary schooling needs to be present in all countries. If not, and if children and adolescents are forced to work, ultimately, community and country development will flag considerably.

The national orphan policy of Botswana is successfully based on the UNCRC. The Kgaitsadi Society in Gabarone is an example of a community organization designed to care for and educate AIDS orphans. Begun in 2002, it addresses children’s basic material needs and provides primary schooling using a flexible model of basic education. The Society also provides support for children caring for other family members and for those who are working.

The parents of many older children and adolescents have died before being able to pass on skills such as farming and animal husbandry. Therefore, job skills training and life skills training for these children are critically needed to increase their options for meaningful, non-exploitative employment and to secure their livelihoods as adults. A joint effort of the World Food Programme and the Food and Agriculture Organization is the Junior Farmer Field and Life Schools. To date, 34 schools benefiting close to 1000 young people ages 12–18 have been set up in Kenya, Mozambique, Namibia, Zambia, Tanzania, Swaziland, and Zimbabwe. The schools teach traditional and modern agricultural methods, as well as HIV/AIDS awareness and prevention, gender sensitivity, sexual health, nutritional education, and business skills. The schools provide psychological and social support, which helps young people develop their self-esteem and confidence.

It is important to remember that there are other groups of vulnerable children, among them those who live with one or both HIV-infected parents (who will most likely be orphans in the near or distant future), those living in households that have taken in orphans, and those who are discriminated against because of the HIV status of their parents or themselves. Taking a child-centric, nondiscriminatory approach is required. Orphan status alone may not be the most important marker of vulnerability. Also, focusing only on orphan status may produce resentment, heighten stigma, and is unfair. A broad range of policies and programs need to be designed to assist all orphans (from all causes), children orphaned by AIDS, and other vulnerable children.

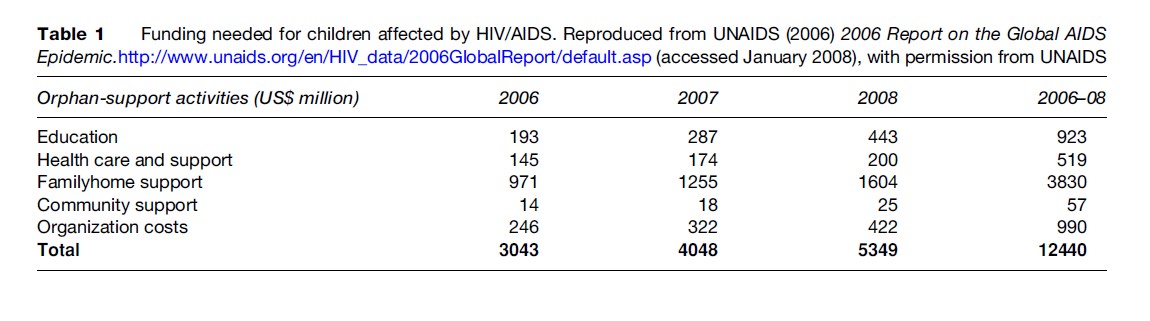

Funding can come from the international community and nongovernmental organizations (see Table 1). Also, individual governments should redirect the money they put toward debt relief into these vital services. Governments need to create and/or improve policies and legislation to protect, support, and strengthen children, families, and communities. Government-sponsored public service announcements and school-based programs can raise awareness and eliminate stigma. And social services need long-term funding commitments from governments and the international community to ensure access. Communities must be involved in the discussion, invention, and implementation of programs for their children. A focus on the futures of children growing up during this pandemic will prevent a generation of ill, malnourished, illiterate, exploited, poor youth at risk of early death. The response requires exceptional dedication, leadership, and resources.

Bibliography:

- Andrews G, Skinner D, and Zuma K (2006) Epidemiology of health and vulnerability among children orphaned and made vulnerable by HIV/ AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Care 18(3): 269–276.

.