Parallel to this recent rise in empowerment, a number of health-care systems have sought to become more patient-oriented. In the United States, a backlash against managed care and the growing number of uninsured and underinsured individuals with limited access to health care has in part precipitated calls for a more consumer directed health-care system. In Europe, where there has been a long history of paternalism extending to medicine and where central agencies ration health care, there has also been an attempt to involve patients in medical decision making and introduce treatment options.

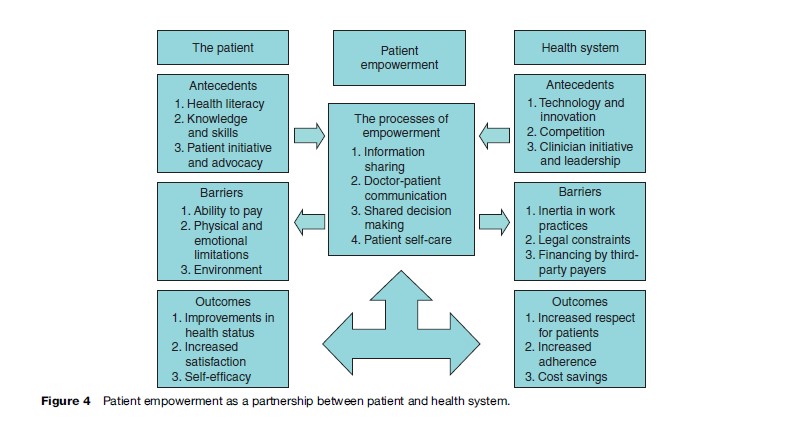

In this section, we present a holistic model of empowerment that focuses on both patient and provider (or system) aspects of empowerment. In this model, patient empowerment is understood as a joint process whereby patients and providers work in partnership to enhance patients’ involvement in their health and health care. This more complex system of empowerment brings together separate literatures on patient and provider empowerment, offering a more comprehensive account of empowerment. More importantly, the model highlights the role that the health-care system plays in patient empowerment. In this regard, patient empowerment is affected by all stakeholders of the health-care system including the state in its regulatory, financing, and purchaser role(s), and the profit and nonprofit sectors in financing, purchaser, and organizing roles. This model (Figure 4) also highlights some of the outcomes related to the fostering and promotion of empowerment for patients and providers.

Processes Of Empowerment In Health Care

With all that has been written about empowerment in health care, little attention has been paid to how empowerment influences or impacts the provision of care. Based on a review of the literature, there are four overlapping themes in the literature that can be considered key processes involved in the empowerment of the patient, namely: (1) information sharing, (2) doctor-patient communication, (3) shared decision making, and (4) patient self-care.

(1) Information Sharing

One of the principal processes of empowerment is information sharing, whether it is among patients, between the patient and physician, or with patients communicating with some external agency/advocate. Traditionally, information sharing efforts related to empowerment were based on grassroots and community programs, however, this has been affected dramatically by national public health campaigns (especially those using mass media), direct-to-consumer advertising, and by email and the Internet. While such broad-brush mechanisms prove to be a cost-effective method for information sharing, small-scale interventions and advocacy continue to play an important role in empowerment. Furthermore, mass media approaches to information sharing lack intimacy, partnership, and follow-up support that are synonymous with grassroots efforts.

For many, the easy availability of information has played an important role in transforming the doctorpatient relationship, while for others, it is a disruptive, potentially unempowering force. This bipolar view of information is best exemplified by the heated debate over direct-to-consumer advertising for pharmaceuticals (Gilbody et al., 2005), but it applies to any number of public health efforts that aim at changing patient behavior. It is certain that with better patient information comes patient responsibility, a responsibility that can be disruptive for many, leading some to classify information sharing as an antecedent to empowerment, rather than an activity of empowerment. Patient empowerment requires that patients are not just recipients of information – from only industry, providers, and government stakeholders communicating with the patient – but agents who can generate and process information. For true patient empowerment, patients need to inform the health-care system about their own situation – both in terms of their health and what they would like out of health care. For example, new technologies, such as home-based monitoring devices, aim to facilitate this empowering process Patients are able to possess real-time knowledge about their (chronic) conditions, which can then facilitate more balanced communication between them and their physicians.

Patients can also possess valuable information in other ways. Self-help groups offer a supportive mechanism for which individuals with similar needs or experiences can be both student and teacher. Also, disease-specific patient associations serve as a valuable meeting place for patients to share information. In the United States, Medicare and Medicaid programs have a specific objective of forming patients about their health-care opportunities – specifically aimed at promoting quality and price transparency.

(2) Doctor–Patient Communication

Focusing on the patient and the doctor, there has been an increasing emphasis on the transformation of the brief patient-doctor encounter into a lasting relationship with the mutual participation of both the patient and physician as the foremost goal. The active involvement of the patient is argued as a means by which problems inherent in health care (including information asymmetry between patient and physician and uncertainty) can be solved through honest and reasonable disclosure. As we move into an era of chronic illness, there is a growing need for better communication between doctor and patient. This interaction is impeded by time and resource constraints, language and cultural barriers, and by the notion (held by some patients and providers) that doctor knows best. While this latter notion has been reinforced by the professionalization of medicine over the past 100 years and the subsequent belief in informational asymmetries, it is also grounded in more ancient archetypes including tribal and religious convictions of the absolute power of the healer/redeemer (i.e., he or she who can give life also has the power to take it away).

Doctor-patient communication can serve both clinical and human needs. By necessity, such communication can be used to understand symptoms and patient histories, but more recently communication is used to understand the patient’s needs and to discuss the optimal treatment path – including introducing the patient to any self-care tasks that they must undertake. On the human side, doctor-patient communication builds rapport and trust, an environment of empathy, and leads to more satisfaction for all parties involved (although a mismatch of patient and physician communication styles might not lead to rewarding communication). Thus, doctor-patient communication is not only vital to informed choice, but it leads to both positive health and nonhealth outcomes for the patient (Pignone et al., 2005).

(3) Shared Decision Making

Given the level of complexity of decision making in modern medicine and the differences between different patients (whether they be caused by variation in disease staging, genetics, lifestyles, or preferences), a shared decision-making framework is becoming increasingly necessary in medicine and a vital step in the empowerment of patients. Here we use shared decision making as an umbrella term to cover the principle of joint, doctor-patient decision making (in the literal sense) and policies, programs, and decision aides that facilitate a thoughtful discussion of health-care options between physician and patient. Given that involvement of the patients in decision making not only has important consequences for their own care (and how he or she feels about it), but also impacts the effectiveness of public health efforts in screening, treatment, disease-control programs, and (potentially) medical costs, a number of agencies now promote active, shared decision making. Surprisingly, there are many who believe that individual patients do not want to be involved in the decision-making process – often sighting ignorance, fear, or cultural barriers. Others believe that if prompted and assisted by an external advocate, these potentially unwilling patients can quickly learn and adopt shared decision making. To encourage such patients to speak up in the medical decision-making process, a number of agencies (both in the profit and not-for-profit sector) offer information about treatment options and decision aides in a range of conditions. A leader in this area is the Ottawa Health Research Institute which has developed numerous ‘patient decision aids’ to help patients and their health practitioners make tough health-care decisions (O’Connor et al., 1999). These decision tools prepare patients to discuss their health care with physicians by informing them about the options and possible consequences, creating realistic expectations, or providing balanced examples of others’ experiences with decision making. Many patient groups now promote shared decision making, often using virtual support groups and storyboards/blogs to share patient experiences. These mechanisms foster doctor–patient communication by enlightening the patient to the various care paths and outcomes that other patients in their shoes have experienced.

(4) Patient Self-Care

One of the elements that best defines an empowered patient is patient self-care or self-management. Again, this encompasses a range of activities from patients triaging themselves to administering end-of-life pain management. It may involve preventative or behavioral change, or thorough self-management of medication for chronic diseases. Patient self-care may not necessarily place the patient in the driver’s seat, but it does make them an important and valued member of the health-care team (as opposed to a passive player who is cared for or operated on). For some, this degree of patient involvement is unusual and infeasible given the lack of knowledge about health care, however, for the vast majority of cases, the patient is the initiator of care (e.g., ‘something is wrong and I have to see the doctor’). Also, for chronic illnesses and other health-care issues that require care over long periods of time or across multiple providers, the patient often becomes the one constant in the healthcare treatment equation. Movements toward patient self-care came to the forefront in areas such as mental health and care for people with disabilities, moving patients from institutional to community care and independent living. As lengths of stay have dropped, particularly in the United States after the adoption of prospective payments, additional care is provided in the patient’s own home (assisted by home health-care services), requiring increased patient self-care. In Europe and Japan, patient self-care is also being promoted in care for the elderly to avoid the prohibitive costs of institutionalized aged care.

Patient self-care promotes personal initiative and responsibility for one’s health, and helps patients make therapeutic choices that are more relevant to their own circumstances and preferences. This said, the ultimate goal of patient care is not just to improve the quality of life, but to increase the effectiveness of care. Existing patient self-management programs are often well monitored and supported by the health-care system, which needs to provide the necessary information, skills, and techniques for patients to be competent in the provision of their self-care. Traditional programs target consumers at risk of declining health or costly medical services through the application of evidence-based care, self-care support, multidisciplinary care coordination, and community collaboration. Self-care is a key to effectiveness and efficiency in the care of chronic disease, like diabetes, asthma, and mental diseases, which can be delivered directly by health-care providers, by specialized disease management organizations, or even by patients and patients’ groups.

Patients’ Role In Empowerment

As seen in Figure 4, the processes of empowerment are affected by both the patient and health-care system. Focusing first on the patient, a number of antecedents and barriers have been identified that support/limit patients’ involvement in the empowerment process. A number of patient outcomes of empowerment have also been identified in the literature.

Patient Antecedents

From the patient’s perspective, there are several antecedents to empowerment, including health literacy, knowledge and skills, and patient initiative and advocacy. Patients must have a degree of health literacy to be active participants in health-care delivery and decision making. Health literacy affects the ability of the patient to comprehend health-care providers and to understand the diagnosis, treatment, and expected outcomes. Patients also need a basic knowledge of health and health care, and the necessary cognitive skills and time to participate when necessary. The final key to patient empowerment is patient initiative: the ability and motivation to become involved in decision making or to marshal the necessary advocacy resources to precipitate change.

Patient Barriers

There are also several barriers that patients face in the road to empowerment, including ability to pay, physical and emotional limitations, and environment. Inability to pay for, or a lack of access to, health-care services is a key destabilizing force in the empowerment process. Patients may be further limited by their mental and health status and by the social environment in which they are situated. Addressing the barriers to empowerment at the individual level can be arguably more complicated, since these barriers concern attitudes and values, which are also often related to the social environment. For example, individuals have different attitudes regarding their willingness to participate in the medical decision-making process. One possible barrier to patient empowerment is that, a priori, patients might feel burdened by the process of decision making for the treatment of their health problems and may prefer to delegate all the decisions to their physician, although such decisions might not fit their needs, preferences, and values. Environment, or what is often referred to in the health systems literature as ‘place,’ also can act as a barrier to becoming empowered. For example, patients in rural or poor, inner-city areas may not only face access barriers to health care, but also have decreased access to education and advocacy groups. Access to both information and services is complicated, and hence often neglected, for people with disabilities.

Patient Outcomes

A range of outcomes of empowerment have been noted in the literature including improvements in health status, increased satisfaction, and self-efficacy. Empowerment has been studied in a number of clinical areas leading to a solid literature linking patient empowerment to better health outcomes, such as for chronic conditions, asthma, and diabetes. Empowerment leads to patient satisfaction given that an empowered patient will have more say in their health care and (more importantly) be aware of the complexities involved in determining the optimal treatment. Some longitudinal studies have also demonstrated the impact of education or self-management training on self-efficacy, which is among the most important outcomes of empowerment. Self-care in particular is an important way in which the patient, instead of the physician, takes control over his or her health, lifestyle changes, and care-seeking behavior, understanding when medical attention is necessary.