All developed countries have established LTC programs under the auspices of health and welfare services, and many developing countries are in the initial stages of some development. Programs usually include some combination of health, social, housing, transportation, and support services for people with physical, mental, or cognitive limitations. However, there is no single paradigm and there are a number of different approaches in the organization and provision of LTC. An understanding of the nature of the variance among countries is important to provide insight for development of care policies.

Countries differ in the way they have resolved basic design issues. Among the most central issues are the nature of entitlements, targeting and finance; service delivery strategies; and issues of integration between LTC and health and social services.

Nature Of Entitlements, Targeting And Finance

Among the most significant key policy design issues are the principles of eligibility for publicly subsidized LTC services and the nature of entitlements. Underlying these issues are two fundamental decisions:

- Who does a country decide to support – everyone or only the poor?

2.. Should access to services be based on an entitlement (insurance principle) or subject to budget constraints (tax-funded principle)?

Such questions also arise in the provision of acute care. What is unique, however, to LTC is the additional possibility that the family might at least in part meet these needs for many individuals. Thus, underlying this determination is society’s view of the appropriate and expected roles of the people with disabilities and their families.

The choice among different options is often between selective (or means-tested) and universal approaches to service provision. Support for the poor is obviously based on a concern for their inability to purchase these services and can lead to an exclusive focus on this group. Even if such is one’s primary goal, this can lead to a strategy that supports the nonpoor, if it is believed that including them in a more universal program is the best way to mobilize support for the poor and to avoid the problems associated with programs for the poor, such as low quality. Support for the broader population can have several rationales, including:

- The catastrophic potential nature of LTC costs when broad segments of the population may find it difficult to pay; when resources are depleted, they become a burden on public programs;

- Concern with the broader social costs of care provision and an interest in easing the burden on families (particularly women);

- Reducing utilization of more costly acute care (particularly hospitalization) services by substituting LTC and in part by medicalizing it.

A second key question is whether access to LTC services should be based on an entitlement or subject to budget constraints. An entitlement program means that, irrespective of available budgets, everyone who fulfills the eligibility criteria must be granted benefits.

Entitlement programs are generally financed through insurance-type prepayments, whereas nonentitlement programs are usually financed through general taxation. A prepayment is generally viewed as granting a right to a service.

It should be kept in mind that an entitlement approach can influence the targeting of services. With contributory entitlement, strict income testing is unlikely to be adopted so as to prevent exclusion from benefits for the many who contribute to financing the program. Nonentitlement programs, focused primarily on the poor, will usually have a relatively strict means test.

The decision to adopt an entitlement approach and a contributory finance system has implications for additional eligibility criteria. The nature of family availability and support will not typically be taken into account in an insurance framework.

A third implication is that under an entitlement system, benefit levels are set relatively lower because family support is not a criterion, and benefits will be provided to many who might already be receiving significant family support. Setting low benefit levels also reflects concern with cost control. In an entitlement system, cost is not easily predictable or defined because it is determined by the number of eligible applicants.

We can illustrate the variation in these fundamental design issues by using a couple of examples. On the one hand, in the UK, provision of LTC is normally income tested and provided on a budget-restricted basis. On the other hand, Scandinavian countries (e.g. Sweden) have a policy commitment to maintaining high levels of services to the entire population and not only for the poor, even though services are financed through general taxation. There are user charges related to income, but given the high level of pensions, this has not been a significant barrier for those who need LTC services. Most Canadian provinces are somewhere in between countries like the UK and the Scandinavian countries with respect to targeting the poor (UK Royal Commission on Long-Term Care, 1999).

The Medicaid program in the United States is an interesting example of a system that while focusing on the poor and financed by general tax revenues provides an entitlement subject to a strict means test.

In recent years, a number of countries have adopted a broader insurance-based approach and a full entitlement. This model includes Germany, Austria, Holland, Israel, and more recently Japan (Brodsky et al., 2000).

Another element of variation among countries is reflected in the actual package of services offered to people with disabilities. There is no universally agreed-upon package of LTC services. For one thing, countries are in different stages of economic development, and some can afford a more comprehensive package than others. In addition, countries have different sociodemographic and epidemiological patterns, cultures, and values, which can all play an important role in defining the needs and priorities. For example, in Sweden most families do not feel obligated to look after older parents, believing that this is just as much the role of government. In contrast, in Israel much more is expected of family members (and less by government).

One of the most important distinguishing dimensions among services is the location in which these services are to be provided, collectively referred to as a continuum of care: home-based, in ambulatory settings in the community, or in a LTC institutional setting.

Home-Based Programs

Such programs may include

- Home health services – include skilled medical/ nursing care, health promotion, prevention of functional deterioration, training and education, facilitation of self-care, and palliative care;

- Personal care – care related with activities of daily living (ADL) (e.g., bathing, dressing, eating, and toileting);

- Homemaking – assistance with instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) (e.g., meal preparation, cleaning, and shopping);

- Assistive devices, physical adaptations of the home, and special technologies (alarm systems).

Ambulatory Settings

Ambulatory settings in the community can provide a different package of services, which may be more health related or more social related. For example, some models of day-care provision focus on health-related services such as monitoring of health status and rehabilitation, whereas others focus on providing the disabled person opportunities for recreation and socialization.

Institutional Services

This model includes a wide range of institutions which provide various levels of maintenance and personal or nursing care. There are LTC institutions aimed mainly at addressing housing needs and providing opportunities for recreation and socialization, whereas others (usually referred to as nursing homes or skilled nursing homes) address health-related needs. The first type serves the moderately disabled, whereas the second type the more severely disabled.

Assistive Living, Service-Enriched Housing, And Sheltered Housing

This model includes special housing units that offer independent living but also services and care to an extent, which, in some cases, comes close to a modern, noncustodial institution. These kinds of sheltered accommodations are now substituting the traditional residential homes, and to some extent also nursing homes.

Whereas almost all industrialized countries offer a broad package of services, the absolute level and the relative importance of the service mix vary. There is also noticeable convergence. In most industrialized countries, the share of the older population (over 65) in institutions varies between 5 and 7%. This percentage does not appear to have grown dramatically in recent years despite continued aging of older populations, and in some countries such as Canada and Holland, it has even declined.

Partly because of the rising cost of institutional care, a focus on community care has taken place in many industrialized countries. ‘Aging in place’ is perceived as preferred by the elderly and, in the majority of cases, as a less expensive alternative to institutional care. One of the hopes of those planning various LTC programs was that their broader availability would reduce costs by reducing acute care hospital utilization and the demand for long-term institutional care. In Japan and Canada, for example, there is an overuse of acute beds by those needing LTC. As a result, reforms have been introduced in Quebec. The Netherlands is one of the countries in which the level of institutional care has been particularly high. The Dutch government has actively implemented experimental programs aimed at reducing institutionalization.

Although the infrastructure of supportive services has grown, the expectation of diverting a significant number of disabled elderly people from nursing homes has been somewhat scaled down in many countries. The extent to which the various LTC programs have influenced patterns of referral to institutions has depended in part on the extent and type of community care available. When such services are limited, they are less likely to offer an alternative to institutionalization, particularly for the more severely disabled elderly.

More recently, some countries have highlighted the potential of health services such as post-acute care and rehabilitation in delaying or preventing long-term institutionalization. Over and above the availability of community services, other factors may affect an elderly client’s ability to choose between community and institutional services, including the supply of beds and the level of copayments for institutional care. In Germany, for example, a copayment of 25% is levied on people entering LTC to keep such care from becoming financially preferable to home care. Japan has made similar efforts to damp down institutional demand.

There is a wide variation in the provision of home care. For example, home help (nursing and assistance in activities of daily living) has been estimated to be provided to between 5 and 17% of the population, depending on the country (OECD, 1999).

In some countries, greater individual flexibility in choice of care delivery has been considered, for example, the provision of cash benefits in addition to or instead of services in-kind. There are three basic forms of provision: services in kind (e.g., Israel); cash allowances without restrictions which enables a client to use the funds as he or she sees fit (e.g., Germany and Austria); and cash allowances with a restriction to purchase services (e.g., experimental programs in Holland and the United States).

Long-Term Care Assessment

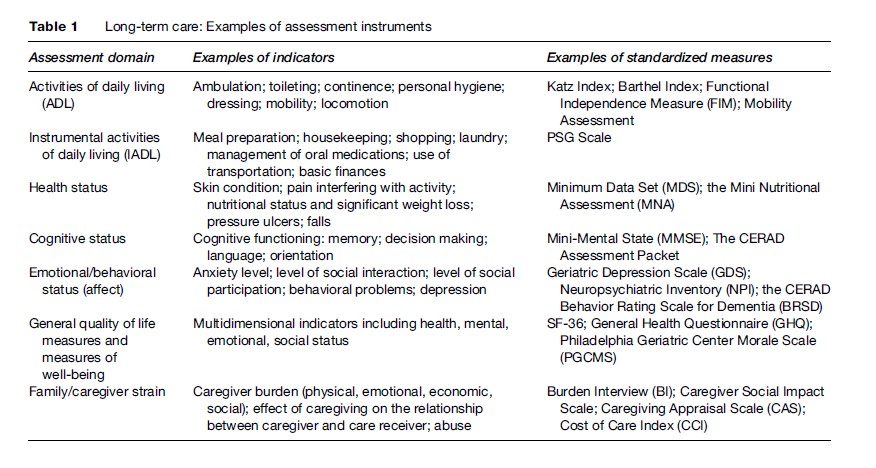

Assessment in LTC serves multiple purposes: to determine eligibility for services, develop the most appropriate care plan according to clients’ needs, monitor clients’ status over time, and assess services’ outcomes in relation to functional needs or maintaining maximum function and enhancing the quality of life of people with disabilities and of their families. At a health-service level, measures may be used to monitor quality of care, allocate resources based on case mix, and even to plan for the development of appropriate resources (Berg and Mor, 2001). The desired characteristics of an assessment instrument will vary relative to the objective of the assessment, but the same instruments can sometimes be used for multiple purposes. Comprehensive assessment should address different domains of impairment (e.g., cognitive status, strength, sensory and perceptual deficits), disability (e.g., measures of activities of daily living), and health related quality of life (e.g., mental health and emotional well-being). For each domain, there is no single best measure. There is general agreement as to the types of domains and indicators that should be included in assessment for long-term care, although the relative weights to be placed on these various domains are more debatable.

There are numerous available assessment instruments that focus on particular aspects of LTC. Table 1 gives selective examples of some of the most established instruments developed in the United States and Europe. Some of these instruments are quite culturally specific and would need to be adapted not only to other languages but also to other cultures and worldviews.

In the United States, Medicare and Medicaid authorities, along with the development of managed care, have given a tremendous push to research in this area (Shaughnessy et al., 1994). One of the best-known LTC assessment tools is the Minimal Data Set (MDS). Its main aim is to provide a reliable, uniform, and universal set of data across settings and for different purposes, which are used to inform care planning to provide a basis for external quality surveys and internal continuous quality improvement and in the case mix adjusted reimbursement systems. Although MDS began in institutions in the United States, it has since been expanded for home care and other settings, and has been used in both English and non-English-speaking countries.

Issues Of Integration Between LTC And Health And Social Services

A major concern involves the continuum of care between the acute and LTC systems, and between the health and social service systems. However, one of the major problems in many countries is fragmentation of such services (Clarfield et al., 2001). The interest in integration arises out of a number of concerns for the quality and efficiency of care. These include the ability to provide for coordinated care packages, consider alternative services in the most optimal way, and ease the access to services by offering one easily identified source of provision. Nevertheless, it is by no means simple to provide integrated LTC because services are the responsibility of many jurisdictions, and the various components tend to work in parallel with separate funding streams and budgets.