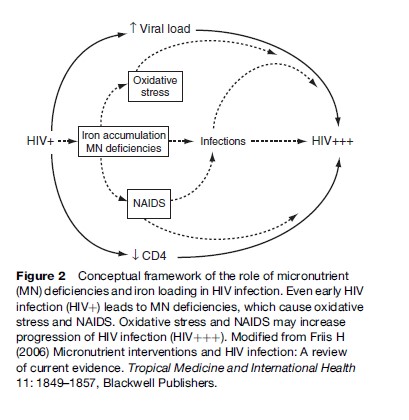

In HIV-infected individuals, micronutrient deficiencies and iron loading may accelerate progression of HIV infection, as shown in the conceptual framework in Figure 2. Deficiencies of antioxidant vitamins and minerals and accumulation of the prooxidant iron could lead to oxidative stress, which is known to activate a transcription factor that increases replication of HIV, which results in increased HIV progression. The iron accumulation may also result in flare-up of latent tuberculosis (TB) and possibly other infections, which stimulate HIV replication. Deficiencies of micronutrients essential to immune functions lead to NAIDS, which could contribute to the risk of coinfections, and to the decline in the number of CD4þ cells, that is, the cells infected and destroyed by HIV. Data from laboratory and clinical studies support this conceptual framework. Accordingly, it is likely that iron supplementation is harmful, as it may increase HIV progression. Yet, iron supplementation is given routinely to pregnant women seeking antenatal care, and occasionally to TB patients presenting with anemia, even in settings where HIV infection is prevalent. It should be a research priority to assess the effects and safety of iron supplementation to people with HIV infection.

In contrast, data from randomized, placebo-controlled trials document a beneficial effect of micronutrient supplementation during HIV infection. For example, among HIV-infected pregnant women in Tanzania not receiving ART, a daily supplement containing high doses of vitamins B, C, and E was shown to increase CD4þ count and to reduce HIV load. After 2 years, those receiving the multivitamins had 29% lower risk of progression to or dying from AIDS (Fawzi et al., 2004). Similarly, a trial among adult Thai males and females with HIV infection found that a daily supplement containing approximately one RDA of a range of micronutrients reduced mortality ( Jiamton et al., 2003). A supplementation trial was also conducted among adult Tanzanian patients with pulmonary TB, of which almost half had HIV coinfection. Supplementation with zinc and other micronutrients in combination, but neither alone, during 8 months of TB treatment considerably increased weight gain and reduced mortality (Range et al., 2005).

This study demonstrates that treatment of an infection, in this case TB, does not eliminate the need for nutritional support, as it is often assumed. In fact, if the infection has resulted in a growth or weight deficit, then treatment, by allowing a growth spurt or weight gain, considerably increases nutritional requirements. If these requirements are not met, then it is likely that the weight gain will result in fat rather than lean body mass. It is also likely that it may exacerbate NAIDS, and potentially worsen the outcome of the infection being treated or of coinfections, such as HIV. Thus, nutritional support providing multiples of the RDA may be needed to meet the requirements during the initial phase of the treatment. Currently, nutritional assessment, advice, and support are rarely integrated in the management of HIV infection and TB in low-income countries.

To the extent nutritional deficiency contributes to progression of HIV and increase in HIV load, then it is also likely to be a determinant of infectiousness, and hence, of mother-to-child or sexual transmission. As such, the supplement containing vitamins B, C, and E, mentioned previously, was also found to reduce mother-to-child HIV transmission, although only among women with signs of poor health. Despite initial observational data suggesting that vitamin A supplementation might reduce mother-to-child HIV transmission, later data from randomized, controlled trials found no effect of vitamin A supplementation in two trials, and increased transmission in a third. The vitamin A supplement contained both preformed vitamin A and provitamin A carotenoids, and it is not clear which of these compounds caused the increase in transmission, and why it was not the case in one of the other trials using a similar intervention (Friis, 2006).

Due to the importance of various nutrients to epithelial integrity and mucosal immunity, it is likely that deficiencies may also affect susceptibility to infection, when exposed to HIV. However, there are currently no data to confirm this.

Nutrition And ART

With access to ART, also for HIV-infected individuals in low-income countries, the role of nutrition–drug interactions becomes increasingly important. According to current treatment guidelines, an HIV-infected individual is only eligible for ART when CD4þ counts are below 350. Since poor nutritional status is widespread even in uninfected individuals, and deteriorates with progression of HIV infection, it is obvious that an HIV-infected individual is in a poor nutritional status at the start of treatment. It is likely that nutritional deficiencies will affect absorption and metabolization of one or more of the two to three different drugs given, and hence affect either efficacy or toxicity of the drugs. Indeed, among patients on ART, low body mass index at the start of treatment has been found to be a predictor of mortality (Paton et al., 2006). Furthermore, it is known from Western countries that some of the ARV drugs affect lipid metabolism, and cause maldistribution of fat (i.e., lipodystrophia) and metabolic syndrome with a high risk of coronary heart disease and diabetes. It is unknown to what extent prior undernutrition and inadequate diet during treatment affect the risk of lipodystrophia and metabolic syndrome.

Breast-Feeding And HIV Infection

Breast-feeding is the healthiest infant feeding practice (Figure 3). The WHO recommends that infants are exclusively breast-fed, that is, given breast milk and nothing else, for the first 6 months of life. Infants should then continue breast-feeding, while also receiving complementary foods, into the second year of life. These recommendations are based on the greater survival of breast-fed, compared with non-breast-fed, infants, in low-income countries (WHO Collaborative Study Team, 2000), but there is also evidence from industrialized countries of improved health. HIV can be transmitted from mother to child through breast milk, but there are data suggesting that early exclusive breast-feeding is associated with a lower risk than mixed feeding (Coutsoudis et al., 2001).

The WHO therefore recommends HIV-infected mothers exclusively breast-feed their infants ‘‘for the first six months of life unless replacement feeding is acceptable, feasible, affordable, sustainable and safe’’ (WHO, 2007: 1). It is emphasized that the risk of HIV infection must be balanced with the risks associated with artificial feeding, and this must be done for each HIV infected woman on an individual basis.

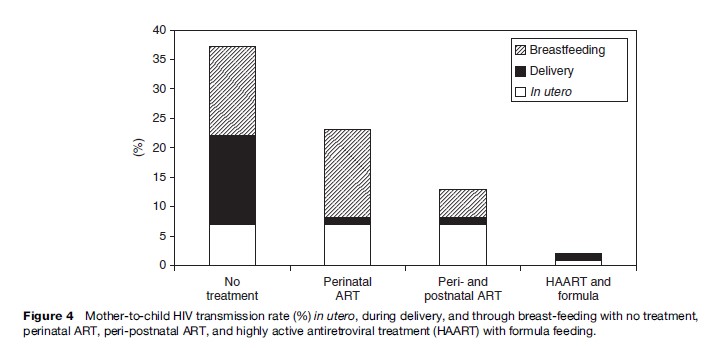

With the increasing availability of perinatal ART in Africa, breast-feeding is becoming the major mode of mother-to-child HIV transmission (Figure 4). The WHO recommendation presents a major challenge because one feeding practice is not universally recommended. Healthcare staff and mothers have to balance the risk of transmitting HIV through breast milk with the risk of infants dying from other infections associated with not breast-feeding.

Several approaches to make breast-feeding by HIV-infected women safer have been investigated but their potential for being scaled up to larger programs is not yet known. One type of approach involves heat or antiviral treatment of expressed breast milk to destroy the virus without destroying nutrients or immune factors in the milk (Israel-Ballard et al., 2005). Another type of approach is to provide ART for the mother or infant during several months of lactation and then cease breast-feeding early, around 6 months (Thior et al., 2006).

Although there have been concerns that breast-feeding may have adverse effects on the health of the mother, possibly as a result of the nutritional stress of lactation, in general, research has not borne this out. As for all lactating women, HIV-infected women who choose to breast-feed should receive appropriate nutritional, medical, and psychosocial support.

The infant feeding advice for HIV-infected women is dependent on the woman’s environment and individual circumstances. Even within a health district there may be differences in the ability of individual women to purchase and safely prepare formula or other replacement foods. The recommended advice also changes fairly rapidly with time as new drugs become available and new strategies are shown to be effective. Health practitioners need to understand and be able to explain the issues associated with both breast-feeding and replacement feeding well enough to guide women in making individual informed choices. For some women, ‘‘acceptable, feasible, affordable, sustainable, and safe’’ infant foods may be available from birth, for others from 6 months, and for women in the poorest, most remote areas, not until even later, if at all. Communicating this advice is challenging and time consuming, especially in a busy maternal and child health clinic. In practice, HIV-infected women in wealthy industrialized countries are recommended to formula-feed, women in the poor rural areas of Africa are recommended to exclusively breast-feed and women in middle-income communities receive variable guidance, depending on the particular health worker and how busy she is at the time, concerning a very difficult choice.

Food Security And HIV Infection

Agriculture is the mainstay of the livelihoods of the majority of people affected by HIV globally. HIV is significantly impacting agriculture, but the interactions go two ways (see Figure 1). The structure of rural communities, the way they govern themselves, the livelihoods on which their households depend, all affect the risks of being exposed to HIV.

The risks people face of contracting HIV will be governed partly by the nature of the livelihood system on which they depend. After HIV has entered a community, the type and severity of its impacts on assets and institutions is then governed by the vulnerability of the system. These impacts will in turn determine the responses that households and communities adopt to deal with this threat. Responses lead to certain outcomes (nutrition and food security being among them) that themselves condition future susceptibility and vulnerability. And so the circle turns