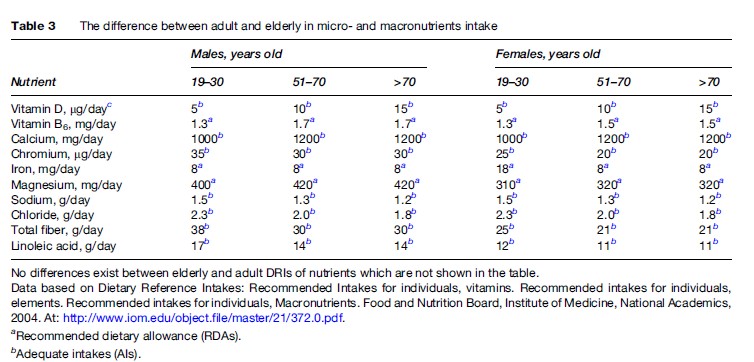

Population-based nutritional surveys show a gradual decline in energy intake in the elderly, accompanied by an increase in energy from carbohydrates and a decrease in energy from fat (van Staveren and de Groot, 2006). The decrease in protein and fat intake in the elderly is associated with mortality, while carbohydrates show a threshold effect on frail elderly patients (Frisoni et al., 1995). The association between BMI and mortality in older adults follows a J-shaped curve, unlike the U-shaped curve in younger adults. The lowest mortality occurred in 60to 90-year-olds at progressively increasing body weight, and higher mortality occurred with lower body weight (Hajjar et al., 2004). Recommended intake for some nutrients in the elderly differs from amounts recommended in adults (see Table 3).

How many calories per day a person over 50 needs depends on his or her level of activity, and it differs by gender: For women, 1600 calories for low level of physical activity, 18000 calories for moderate activity, and 2000–22000 calories for an active lifestyle; for men, 2000 calories, 2200–2400 calories, and 2400–2800 calories, respectively (National Institutes of Health, 2005).

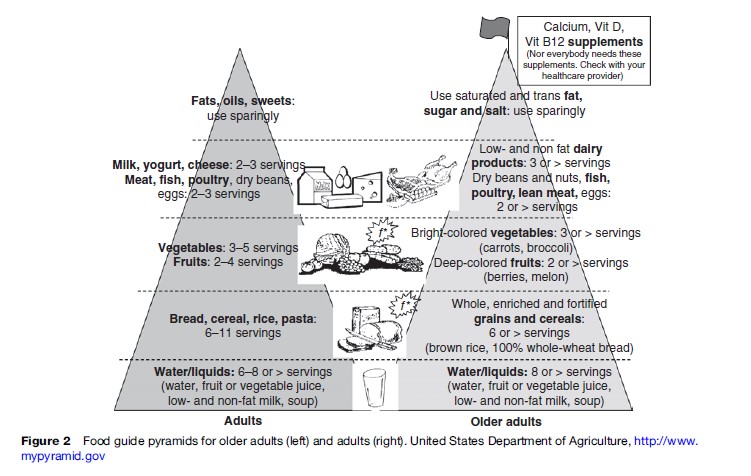

Since 1992, Food Pyramids for different groups of the population and for different cultures and countries have been created, including a specialized pyramid for older adults. Several points are stressed in the Food Pyramid for the elderly (see Figure 2). For the elderly, special considerations are calcium, vitamin D, vitamin B12, salt control (especially for persons with hypertension), lactose-free dairy products (or lactose added to milk in case of enzyme deficiency), lean meat and skinless poultry, high-fiber food (helps to promote stool regularity, of great importance for the elderly), and a sufficient amount of fluids to prevent dehydration.

Assessment Of Nutritional Status

Malnutrition is a common but a frequently underdiagnosed condition among the elderly. Consequently, in European countries and in the U.S. nearly 25–60% of hospitalized old people and 10–85% of nursing home residents have malnutrition of varying severity. Profound malnutrition and serious illness often present concurrently, accelerating each other. Malnutrition has been used to refer to a wide range of deficiencies, including protein energy, vitamins, fiber, water, as well as their excesses (obesity, hypervitaminosis). Detection of malnutrition is based on the patient’s history, physical examination, and laboratory evaluation.

Clinical manifestation: Delayed wound healing, development of pressure ulcers, susceptibility to focal and systemic infections, cognitive decline, delayed recovery from acute illness.

- History: Patient’s food diary (simple questionnaire) includes information about risk factors for deficient nutrition intake.

- Physical exam: General body habitus, body weight and height, presence of any sign of nutritional deficiency in the skin, hair, nails, eyes, mouth, and muscles. Involuntary weight loss of 5% or more in 1 month or 10% or more in 6 months is a sign of malnutrition in old age (Dempsey et al., 1998). The desired BMI for older people is 24–29 kg/m2 (compared with 20–24 kg/m2 in younger persons), and BMI under 24 kg/m2 is an indicator of malnutrition. However, BMI may not be as informative in the elderly as at younger ages because an older person’s stature often cannot be measured accurately be- cause of increased prevalence of spinal curvature; for these individuals estimation of stature from knee height is better for providing accurate information. Calf circumference is a more sensitive measure of the loss of muscle mass in the elderly compared with other circumferences and skin-fold thickness (Hajjar et al., 2004).

- Laboratory evaluation: Serum albumin levels under 3.5 g/dl are suggestive of protein energy malnutrition, albumin level under 3.2 g/dl is a predictor of mortality and morbidity in the elderly. Total lymphocyte count (TLC) less than 800 cells/mm indicates severe malnutrition.

However, no single physical or laboratory finding is a sufficient determinant of malnutrition. This is why several tools have been developed to evaluate malnutrition:

- The Instant Nutritional Assessment (INA, includes TLC, albumin, and weight change);

- The Subjective Global Assessment (SGA, combines information from the patient’s history, physical examination, and the clinician’s judgment);

- The DETERMINE checklist (developed as a screening and public awareness tool);

- The malnutrition risk scale (SCALES, was developed as an outpatient screening tool; it includes sadness, cholesterol, albumin, weight loss, eating problems, and shopping);

- The Mini-Nutritional Assessment (MNA, a screening tool of choice for many geriatricians, it includes anthropometric, general, dietary, and self-assessment parameters and does not require laboratory tests);

- The Department of Veterans Affairs defines malnutrition as meeting two of the following four criteria (weight–height ratio <90% of normal, mid-arm muscle circumference <90% of normal, albumin <3.5 g/ dl, transferring <200 mg/dl) (for detailed information about these tools, see Committee on Nutrition Services, 2000; Hajjar et al., 2004).

Dietary Supplements For The Elderly

Vitamin and mineral deficiencies often occur in elderly persons and are exacerbated during hospitalization, hypermetabolic states, alcohol use, liver disease, diuretic use, and laxative abuse, and deficiencies in this group should be corrected by food and dietary supplements. Randomized control trials do not support use of vitamin and mineral supplements by well-nourished individuals ( Joshi and Morley, 2006). Consequently, at present there is no significant proof that large doses of antioxidants can prevent chronic diseases associated with aging (such as CVD, diabetes mellitus, and cataracts). Results of nine placebo-controlled double-blind studies of multiple nutrients in the elderly, as well as 12 placebo-controlled studies with a single nutrient intervention, showed a trend of improvement in the nutritional status of the elderly, i.e., serum vitamin levels and some biochemical parameters (van Staveren and de Groot, 2006). It is acceptable for old persons to supplement with vitamin B12, calcium, vitamin D, iron (extra for postmenopausal women who are using hormone replacement therapy) and vitamin B6.

However, the doses of micronutrients should not exceed the recommended daily intakes, because adverse events associated with dietary supplements have been reported, with symptom severity increasing with age (Palmer et al., 2003).

Problem Of Food Safety In The Elderly

Old people may have problems identifying tastes and smells, and this makes food freshness control more difficult. To avoid this problem, old people should fully cook eggs, pork, fish, shellfish, and poultry and should avoid deli meats and nonpasteurized food, including dairy products.