It has long been suggested that OSAS is associated with a significant morbidity and mortality and that it presents a major public health burden. Excessive daytime sleepiness is the most common daytime symptom of OSAS and leads to a variety of potentially serious sequelae. Patients with OSAS have significantly impaired quality of life and social functioning, as well as a higher rate of minor psychiatric illnesses such as anxiety and depression (Engleman and Douglas, 2004). Furthermore, various studies utilizing objective assessments identified significantly reduced cognitive performance in OSAS patients in comparison to controls. As a further consequence, the rate of road traffic, as well as work-related accidents, is three to seven times higher (Stoohs et al., 1995). However, the EDS and associated consequences of OSAS are reversible with effective continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment.

The principal physical morbidity and mortality of OSAS, however, relates to the cardiovascular system. The association is particularly strong with systemic hypertension, and large population-based studies have yielded convincing evidence of a modest but definite association, independent of possible confounding factors such as age, sex, or obesity. The Sleep Heart Health Study, which included over 6000 subjects undergoing in-home polysomnography (PSG), identified a modest association (odds ratio (OR) 1.37) increasing with greater severity of the disease (Nieto et al., 2000). The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort study employing 1069 subjects with in-lab PSG identified an even stronger correlation with an OR of 3.1. Moreover, a prospective follow-up of this population demonstrated that subjects with an AHI of 0–4.9, 5–14.9, and over 15 events/hour of sleep had ORs of developing systemic hypertension over the next 4-year period of 1.42, 2.03, and 2.89, respectively, compared with matched control subjects without OSAS (Young and Peppard, 2000). Data linking OSAS to other cardiovascular diseases are not as persuasive, but the evidence of an association is growing. Indeed, in the Sleep Heart Health Study cohort, OSAS emerged as an independent risk factor for congestive cardiac failure (CCF) (OR 2.2), cerebrovascular disease (OR 1.58), and coronary artery disease (CAD) (OR 1.27) (Shahar et al., 2001). Furthermore, effective CPAP therapy decreases cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, as demonstrated in large long-term cardiovascular outcome studies (Doherty et al., 2005; Marin et al., 2005).

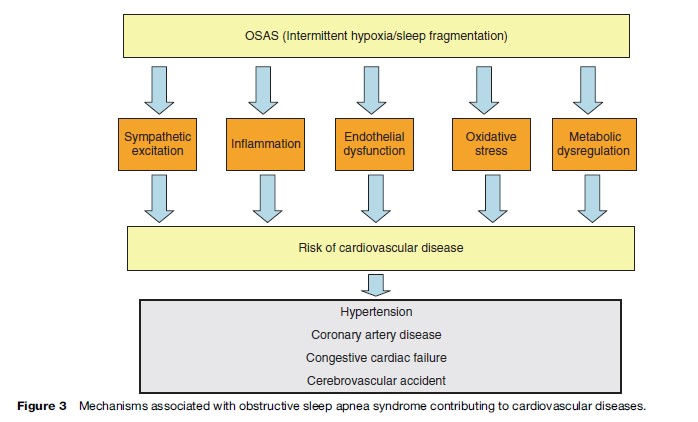

The mechanisms by which OSAS predisposes to cardiovascular disease are not fully understood but is likely to include sympathetic excitation, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction in addition to metabolic dysregulation (Figure 3). The typical cyclical pattern of intermittent hypoxia and reoxygenation associated with OSAS probably plays a significant role in the pathophysiology as it selectively activates inflammatory over adaptive pathways with the downstream consequence of the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFa), which has been demonstrated to be involved in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis (Ryan et al., 2005).

Management

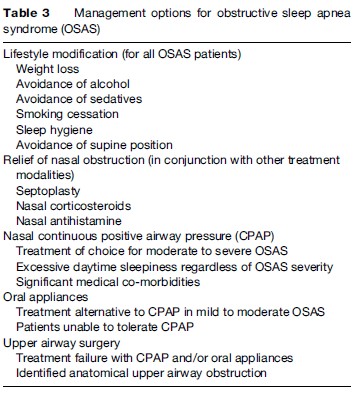

Management options for OSAS are outlined in Table 3. The most widespread and effective treatment modality is CPAP, but milder cases of OSAS can often be managed by conservative measures. These include weight loss (where appropriate), sleep hygiene, alcohol avoidance, relief of nasal congestion, and measures to keep the patient off his or her back (since most cases of sleep apnea tend to be worse when the patient is supine). Only a minority of adult cases has a correctable anatomical lesion obstructing the upper airway, but the majority of children with OSAS have enlarged tonsils and adenoids, and surgical removal of these tissues can resolve the condition in many cases.

Conservative Management

Weight Loss

As mentioned previously, approximately 70% of OSAS patients are obese, that is, exhibiting a body mass index (BMI) of more than 30 kg/m2. Weight loss has definite beneficial effects and results in improvement, or occasionally disappearance, of sleep-related breathing disorders in many patients. Weight loss is difficult to achieve but more particularly to maintain. However, in all cases, weight loss should be encouraged in obese OSAS patients. Weight loss also has beneficial effects on snoring.

Avoidance Of Alcohol And Other Respiratory Depressants

Ethanol suppresses upper airway dilator muscle activity, which predisposes to obstructive apneas and also prolongs the duration of apneas and enhances the associated oxygen desaturations. Similar effects have been reported with other respiratory depressants such as diazepam. Patients with OSAS should therefore be counseled to avoid alcohol, particularly within 3–4 h of retiring to bed, and also sedative medications.

Smoking Cessation

Smoking is a risk factor for OSAS, probably secondary to the increased upper airway resistance as a consequence of nasal mucosal inflammation. Therefore, current smokers who have been diagnosed with OSAS should be advised to quit. However, the weight gain that frequently follows smoking cessation should be actively avoided.

Sleep Hygiene

Sleep fragmentation and sleep deprivation could exacerbate OSAS, as they reduce ventilatory responses to hypoxia and increase upper airway collapsibility. However, controlled trials specifically targeting the impact of sleep hygiene on OSAS are lacking. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to advise patients of the possible interaction between poor sleep hygiene and OSAS. Avoidance of caffeine, a regular sleep–wake cycle, measures to optimize sleep environment, and avoidance of daytime napping are among the general recommendations to improve sleep hygiene.

Sleep Position

It has been long recognized that snoring patients do so most loudly in the supine position. Similarly, it has been demonstrated that a large proportion of unselected patients with a diagnosis of OSAS demonstrate a lower rate of apneic events in the lateral compared to the supine position. A tennis ball sewn into the pyjama top at the midthoracic level was one of the first means used to prevent sleep in the supine position. Two other strategies have been used, namely sleep position training using a posture alarm device and a tongue-retaining device in order to prevent tongue retrolapse when the patient sleeps in a supine position.

Relief Of Nasal Obstruction

Nasal obstruction due to anatomical abnormalities or chronic congestion is a common complaint among patients with OSAS and predisposes to UA occlusion during sleep. However, treatment modalities to relieve nasal obstruction have failed so far to demonstrate a clear benefit. In selected patients, relief of nasal obstruction by surgery, nasal steroids, or antihistamines may improve symptoms and should be considered as treatment options.

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Therapy (CPAP)

The current management of moderate to severe OSAS is largely dependent on nasal CPAP (nCPAP), which acts to splint the upper airway open during sleep, and thus counteracts the negative suction pressure during inspiration, which promotes upper airway collapse in these patients. Nasal CPAP completely controls the condition and has a dramatic effect on the patient’s awake performance because of the normalized sleep pattern. CPAP improves quality of life, neurocognitive function, and driving performance (Jenkinson et al., 1999). Moreover, long-term cardiovascular outcome studies have demonstrated significantly fewer cardiac events in CPAP-treated patients in comparison to nontreated subjects. Although nCPAP is highly effective in controlling OSAS, the device is cumbersome, and compliance data show only moderately satisfactory results. Compliance relates positively to the severity of OSAS and level of daytime sleepiness.

Oral Appliances

Oral appliances are an alternative to CPAP therapy in patients who have failed or refused this treatment modality and also as initial therapy in patients with milder disease. The goal of therapy with oral appliances is to modify the position of UA structures in order to enlarge the airway, reduce resistance, and presumably reduce UA collapsibility. The effects on UA muscle function may also be important due to the changes in direction of muscle fibers. Although randomized studies have demonstrated benefit in improving objective and subjective sleep parameters, CPAP is significantly more effective. However, patients generally prefer oral appliances. More data are needed for neurocognitive and cardiovascular outcomes after treatment with oral appliances.

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty

The objectives of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) are to enlarge the oropharyngeal airway and reduce the collapsibility of this particular segment of the UA. In OSAS patients, UPPP indications should be restricted to those with mild disease and evidence of retropalatal narrowing, and careful patient assessment and selection is very important. It should also be remembered that by increasing mouth leaks, UPPP might compromise CPAP therapy and reduce the maximal level of pressure that can be tolerated.

Conclusion

OSAS is a highly prevalent disorder that can have major adverse consequences on the health and quality of life of the affected patient. However, the disorder is eminently treatable, and successfully treated patients generally report a dramatic transformation in their quality of life.

Bibliography:

- Davies RJ and Stradling JR (1990) The relationship between neck circumference, radiographic pharyngeal anatomy, and the obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. European Respiratory Journal 3: 509–514.

- Doherty LS, Kiely JL, Swan V, and McNicholas WT (2005) Long-term effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy on cardiovascular outcomes in sleep apnea syndrome. Chest 127: 2076–2084.

- Engleman HM and Douglas NJ (2004) Sleep, 4: Sleepiness, cognitive function, and quality of life in obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Thorax 59: 618–622.

- Jenkinson C, Davies RJ, Mullins R, and Stradling JR (1999) Comparison of therapeutic and subtherapeutic nasal continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea: A randomised prospective parallel trial. Lancet 353: 2100–2105.

- Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, and Agusti AG (2005) Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: An observational study. Lancet 365: 1046–1053.

- Mezzanotte WS, Tangel DJ, and White DP (1996) Influence of sleep onset on upper-airway muscle activity in apnea patients versus normal controls. American Journal of Respiratory Critical Care Medicine 153: 1880–1887.

- Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, et al. (2000) Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. Journal of the American Medical Association 283: 1829–1836.

- Remmers JE, deGroot WJ, Sauerland EK, and Anch AM (1978) Pathogenesis of upper airway occlusion during sleep. Journal of Applied Physiology 44: 931–938.