Work-Related Injury And Disease Deaths In Various Countries

Injury

Work-related fatal injury is a high-profile issue in many countries, both developed and developing. Overall estimates from studies have been produced for various countries, including Australia, Denmark, Finland, Jordan, New Zealand, and the United States. Most of these studies counted the number of injury deaths using coroners’ data and/or death certificates. All of the studies included workplace deaths, most included work-road deaths, and some included commuting deaths. Countries and regions for which one or more detailed study or review articles addressing work-related fatal injuries have been published include Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Denmark, Europe, Finland, Iceland, Italy, Jordan, Kuwait, New Zealand, Nigeria, Scandinavia, South Africa, Sweden, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Comparisons between studies or countries of rates and types of fatal work-related injuries have many potential pitfalls. These arise because of differences in the definitions of work relatedness, and differences in the inclusion and exclusion criteria, which may be based on age, sex, occupation, industry, employment arrangement, or incident type. Even when the definitions and criteria are apparently similar, appropriate comparisons should be undertaken on a limited, well-defined basis, such as using industry, occupation, and/or age, or using overall results adjusted for differences in these potential confounders. A recent example of a comparison that attempted to take account of the factors compared fatalities in New Zealand, Australia, and the United States. In this study, the raw fatality rates per 100 000 persons per year were 4.9 (New Zealand), 3.8 (Australia), and 3.2 (United States). Most of the differences were found to be due to differences in industry distribution. Once this was taken into account, the Australian and U.S. rates were found to be very similar, and the New Zealand rate was found to be only 10 to 15% higher (Feyer et al., 2001). Other studies have compared New Zealand with other countries, the United States with Australia, Great Britain with Europe and the United States, or have compared results between countries as part of analyses that focused on specific industries, occupations, or factors.

Disease

National estimates of work-related disease deaths have been produced for Australia, Canada, Finland, New Zealand, and the United States. All these studies relied on the PAR approach to produce their estimates. Direct comparison between countries is not common and has the same problems as comparisons on the basis of injury, with these problems usually more important and harder to overcome when studying disease.

Common Characteristics Of Work-Related Fatal Injuries And Diseases

The ultimate aim of the study of work-related injuries and diseases is to prevent their occurrence. General surveillance and maintenance of national statistics makes an important contribution to this by providing an understanding of the frequency and rate of such deaths, changes in these parameters over time, and differences between different regions, industries, occupations, or countries. All of these may provide evidence of approaches to prevention that are apparently successful or not successful, or identify hazards and associated risks that need to be controlled. However, the design of appropriate interventions requires a thorough understanding of the circumstances surrounding fatal incidents, looking for common patterns that might be amenable to preventative interventions. Such an understanding usually only comes from a detailed study of a well-circumscribed area, focusing on factors such as a particular industry, occupation, mechanism, agency, exposure, or personal characteristic. There have been many examples of studies that have focused on such areas. This section summarizes the main approaches that have been taken.

Injuries

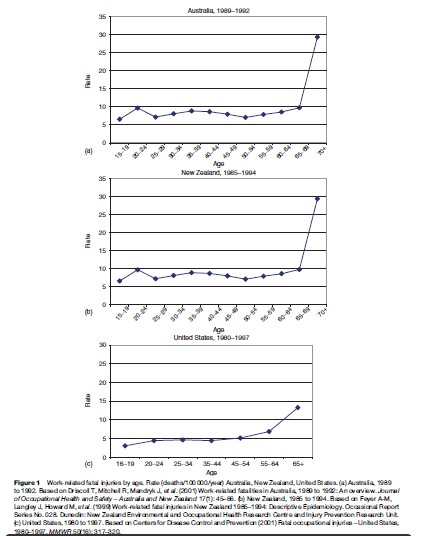

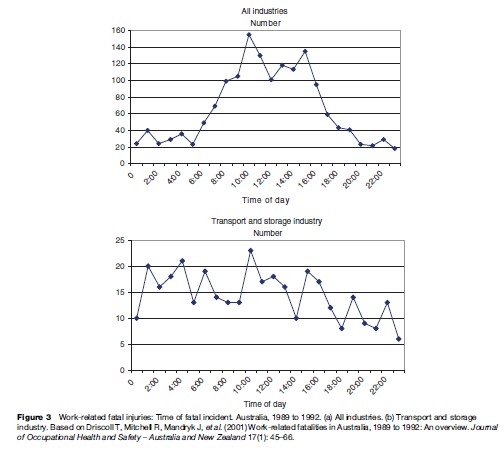

Published studies of work-related fatal injuries may include all work-related injury deaths or may focus on particular regions, industries, occupations, mechanisms, involved agencies, injury type, personal characteristics, human factors, intent, place of injury, and specific injury circumstance (see Table 1 for selected examples). Some of the important findings arising from these studies are considered here.

Age And Gender

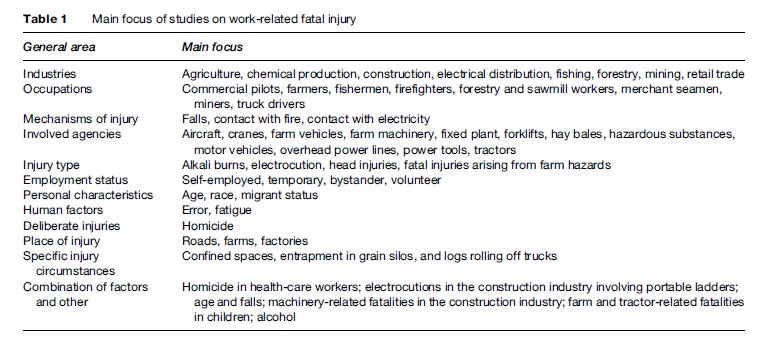

Most studies have found a much higher rate of work-related fatal injury in men than in women. However, this is probably mainly a result of differences in the type of job (the occupation, specific task, and industry) performed by them. Similarly, most studies have found that the rate of work-related fatal injury is fairly constant until about the age of 60 or 65, after which time the rate of injury increases dramatically (see Figure 1). There are a number of plausible explanations for this finding, including older people being more likely to be injured or to die from a given injury than younger workers. However, it may also be partially artifactual, resulting from undercounting in the number of people at risk (i.e., older working people may not have been properly recorded as part of the labor force). This is especially an issue for elderly farmers, who may continue to work but not be recorded as workers in population surveys, thereby producing an erroneously low denominator and a correspondingly erroneously high fatality rate. There is also a worrying number of deaths of young workers associated with farm work.

Industry And Occupation

Certain occupations and industries have been consistently found to have a high rate of work-related fatal injury (see Table 1). The occupations include commercial pilots, loggers, fisherpersons, miners, truck drivers, and farmers. High rates are commonly seen in the forestry and logging, fishing, mining, agriculture, transport, and construction industries. These high rates presumably reflect high risks of exposure to serious hazards. It is usually more valuable to examine occupation (what people do) rather than industry (where people work), because the risks are usually similar in the same occupation regardless of industry (e.g., truck drivers in the agriculture, manufacturing, mining, and transport industries probably face similar hazards and associated risks). In contrast, a single industry usually comprises a range of occupations with very different risks (e.g., an office worker, an electrician, a driver, and a painter all employed in the same construction company would generally face different hazards). Within each area it is helpful to use as narrowly defined subgroups as the data will allow. For example, the high rates for forestry, mining, and structural steel laborers and fishermen/ women are hidden by the overall rate for the relevant larger occupation group to which they usually belong (‘Laborers and related workers,’ or something akin to this).

Mechanism

Vehicular incidents on public roads are often found to be the most common single mechanism of fatal incident for most occupation groups and many industry groups. Falling from a height, falling objects hitting persons, and contact with electricity are other common mechanisms seen across a number of different occupation and industry groups (see Figure 2).

Place

Work-related fatal injuries in persons from particular occupations or industries occur in many different places, so a single place such as a farm or a mine is not a very sensitive indicator of fatalities in specific occupations or industries such as farming or mining. However, some places are likely to have a high specificity for work-related fatal injuries. For example, the vast majority of nonsuicide fatal injuries occurring in mines or on farms are likely to be related to work or work-related exposures, but many injuries occurring to farmers do not occur on farms, and many injuries to miners do not occur on mine sites. Motor vehicle incidents are usually the most common single mechanism resulting in the fatal injury of working persons, and it is not surprising that the most common place for these fatal incidents is public roads of some sort. However, many vehicle incidents also occur in other workplaces, such as farms, trade areas, and mines.

Cause Of Death

The cause of death is likely to vary with the circumstances of the incident. So, although knowledge of the cause of death is helpful when identifying opportunities for, and approaches to, prevention, such information is best combined with other relevant information. For example, in a study of work-related fatal injury in Australia, mechanical asphyxia accounted for 7.4% of all deaths and 7.9% of workplace deaths. However, it was the cause of death in 45% of deaths involving persons being trapped by machinery, 25% of deaths involving the rollover of mobile mechanical equipment, and 17% of deaths involving persons being hit by falling objects (Driscoll et al., 2001). This type of information is important because such incidents are potentially survivable if the person has not sustained severe injuries. In many of these incidents, the worker was working alone, and it is possible that the worker may not have died if there was someone else nearby at the time of the incident who could have freed the injured worker. This has implications for the working procedures used in particular situations (e.g., whether persons are allowed to work alone) and in assessing the possible usefulness of systems for contacting someone in the event of an emergency.

Alcohol And Drugs

The role of alcohol and drugs in work-related fatal injury is controversial. Most studies have found that alcohol and drugs contribute in a meaningful way to about 5% of the deaths of workers. Alcohol is probably a larger problem than drugs, but the relative contribution is likely to vary between working circumstances. For example, stimulant use is likely to be more widespread, and more likely to contribute to injury occurrence, in truck drivers than in many other occupations. Since alcohol and drug use in connection with work is potentially preventable through appropriate education and other programs, alcohol and drug use should be considered in occupational health and safety (OHS) prevention programs.

Time Of Day

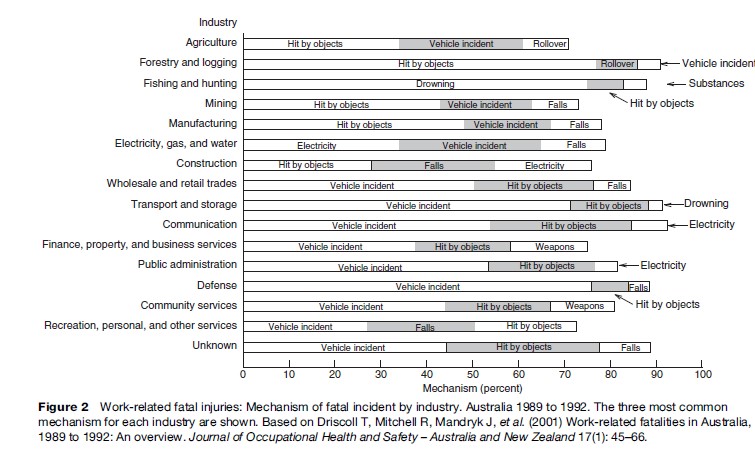

Most studies that have examined the time of day of fatal incidents have found mid-morning and mid-afternoon peaks. This has been seen across many industries (e.g., fishing, forestry, and mining) and reported by a number of studies. It is likely that the main reason for this pattern is that these are the times when the largest number of people are working, implying that the risk to the individual worker is no higher than at other times (unfortunately, appropriate denominator data are rarely available, meaning that rates can’t be calculated). An alternative explanation, which might make some contribution, is that the peak times may be when the activities are more complicated or interact more, when people are becoming fatigued several hours after the last break or meal, when people are anticipating a break, or some combination of these or other factors. For other industries, such as the transport industry, the time of the fatal incident is usually more evenly spread across 24 hours, presumably reflecting the fact that the transport industry functions at a high level at most hours (see Figure 3). However, it should also be kept in mind that fatigue appears to be an important problem in long-distance truck drivers, and so higher relative frequencies of incidents occurring overnight might reflect a much greater risk for drivers during these early morning hours, with fatigue and darkness plausible explanations for this.

Diseases

As for injury, published studies of work-related fatal disease may include all work-related disease deaths or focus on particular diseases such as cancer, heart disease, infectious disease, neurological disease, and so on. Studies have also focused on particular regions, industries, occupations, and exposures.

Disease Types

On a global basis, malignant neoplasms, communicable diseases, circulatory diseases, and respiratory diseases are the main causes of work-related fatal disease (Driscoll et al., 2005a; Hamalainen et al., 2007). In the WHO Comparative Risk Assessment project (which could not include a consideration of communicable diseases and some other diseases because the global data were inadequate to allow the Comparative Risk Assessment methodology to be applied), the main causes of disease mortality were found to be chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (59% of occupational disease deaths), lung cancer (19%), mesothelioma (8%), asthma (7%), coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (3%), silicosis (2%), asbestosis (1%), and leukemia (1%) (Concha-Barrientos et al., 2004).

Age And Gender

Fatal occupational disease is nearly exclusively a problem of older and retired workers, apart from deaths from communicable disease. This is because the conditions likely to prove fatal usually have a long period between exposure and when the condition becomes evident. As with injury, rates of most types of work-related fatal disease are much higher in men than in women, and this almost certainly reflects the type and level of their respective exposures at work. One exception to this is communicable diseases, which are estimated to be much more common in women than men as a cause of work-related mortality, especially in developing countries where women work in occupations with a high risk of exposure to infective agents (Hamalainen et al., 2007).

Industry And Occupation

Certain occupations and industries have associated harmful exposures that significantly increase the risk of developing a condition that leads to premature death. High-risk exposures that have been a major problem in the recent past include asbestos (in mining, manufacturing, and construction), silica (mining and construction), benzene (manufacturing), chlorinated organic solvents (manufacturing), and pesticides (farming). Most of the more obvious causative exposures that typically caused cancer or severe lung disease are now well-controlled in the majority of workplaces in developed countries, but control is still poor in many developing countries and is not always optimal in developed countries. In addition, less obvious issues have been recognized, such as the balance between job demands and job control, that have been found to be associated with the development of ischemic heart disease and, because ischemic heart disease is so common, to result in a considerable number of work-related deaths.

Nonfatal Injury And Disease

Injury

The Connection Between Fatal And Nonfatal Injury

The circumstances surrounding fatal work-related incidents are probably representative of the circumstances surrounding many major nonfatal injuries and probably many minor injuries and near misses, but appear not to be representative of all injuries. For example, certain nonfatal injury types such as injuries of the back from sprain/ strain, overuse injuries of the limbs, and simple cuts from hand tools rarely cause death. However, for many other injury circumstances, it is probably just a matter of chance as to whether the affected person is killed, injured, or just involved in a near miss. Common examples of this include most electrocutions, falls, and drowning, as well as most injuries resulting from motor vehicle incidents or the use of fixed or mobile mechanical equipment. In addition, for the vast majority of nonfatal injuries, there is little or no useful information recorded by the workplace, and even fewer nonfatal injuries are investigated by OHS jurisdictions and/or the police. Even where incidents are investigated, the data are usually not available in a form that facilitates systematic study. Therefore, more is known about fatal injury, and the study of fatal injury also provides information on factors that are relevant to many nonfatal injuries.

Lost time injury measures (which count injuries that result in one or more days off work) are commonly used to monitor levels of OHS. However, the measures are open to manipulation and subject to deliberate or unintentional variations in reporting efficiency, making interpretation and comparisons more difficult. In contrast, deaths are hard to cover up or ‘lose.’ Also, although both fatal and lost time injury end points can have some definitional problems, with death these problems are on the margins, whereas with nonfatal injury the definitional problems can be of major importance.

One consistent difference is in the relationship to age, with the rate of nonfatal injuries being highest in young workers. Much of this difference is probably due to the varying risks faced by workers of different ages, but higher rates have still been found even when differences in job characteristics are taken into account.

The study of nonfatal injury and fatal injury should be seen as complementary. For year-to-year measures within a company or small industry group, nonfatal injury (or some form of process measure) is the appropriate outcome to use. Whether this outcome is defined further as the lost time injury rate, or in some other form, is less of an issue. However, for national or international comparisons, for industry comparisons, for occupational comparisons, and for identification of common circumstances or patterns associated with incidents that result in injury, information on work-related fatal injury, usually obtained from some form of coroner’s system, is the most reliable form of data to use to monitor general levels of OHS related to most forms of injury.

Common Characteristics Of Work-Related Nonfatal Injuries

Studies of nonfatal work-related injury have a similar focus to studies of fatal injury, except that there are few studies at the international or even national level. As mentioned, many serious nonfatal injuries are similar in nature, character, and circumstance to fatal injuries, but there are also some types of injuries that are rarely or virtually never fatal. In addition, the identified characteristics of work-related nonfatal injury depend considerably on the working group being studied and the data source being used (e.g., workers’ compensation data, hospital emergency department data, hospital admissions data, or data from a specific cohort of workers). Key aspects of nonfatal injuries that differ from fatal injuries are that the common injury types across most industries are laceration, fracture, or sprain/strain of the hands (including the fingers) and injuries to the eye, most commonly by foreign bodies. In some industries and occupations, sprain/strain of the back is also common. Common characteristics of the circumstances associated with these injuries are using powered or non-powered tools (hand and eye injuries) and manual handling of heavy objects or working with repetitive or awkward postures.

Disease

The Connection Between Fatal And Nonfatal Disease

Many of the causative exposures and exposure circumstances leading to fatal disease can also lead to nonfatal disease, either resulting in the same condition or related conditions. For example, exposure to asbestos can lead to malignant mesothelioma, which is nearly always fairly rapidly fatal; lung cancer, which is often fatal but not always so; and asbestosis, a fibrotic disease of the lung that can be fatal but more commonly isn’t, although it can result in severe disability due to respiratory disease. Exposure to ultraviolet radiation can lead to malignancies of the skin, which are more commonly not fatal than fatal. There are a wide variety of occupational exposures that can cause or exacerbate the symptoms of asthma, the severity of which can vary between mild, debilitating, or even fatal. Dermatitis due to work exposures can be mild or very debilitating but is very rarely fatal. Much disease related to work, whether fatal or nonfatal, is hard to identify as being work-related because of the long latency between exposure and disease diagnosis, and because most diseases can be caused by more than one exposure. The available records usually provide better coverage of disease deaths than nonfatal disease cases, especially in developing countries, but for most disease types the connection to work is difficult to establish regardless of the severity of disease. Therefore, study of fatal disease deaths also provides information on factors that are relevant to many nonfatal diseases, but study of nonfatal disease is still necessary because some diseases rarely, if ever, lead to death and the connection to work is hard to identify for disease deaths. As for injuries, the characteristics of work-related nonfatal disease depend considerably on the working group being studied and the data source being used. Respiratory disease, ischemic heart disease, musculoskeletal disease, noise-induced hearing loss, and dermatitis are key nonfatal diseases, with the latter three in particular not a feature of fatal work-related disease. As indicated by the global estimates, these diseases result in a huge burden of work-related ill health.